The bell Martha (1748-1782), white wife of Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) used to summon Sarah Hemings (1773-1835, Sally), given to Sally by a dying Martha: Sally was among those who tended Martha during her death agon

Dear readers and friends,

I read on about what I find I must call Jefferson’s women and men after

finishing Kierner’s biography of Jefferson’s oldest white daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph , and watching and reading about the sources for the Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala film, Jefferson in Paris. By chance during the more than 3 weeks it took me to read G-R’s Hemingses of Monticello Henry Wieneck’s Master of the Mountain was published and prompted yet another spate of denunciation of Jefferson.

The Hemingses of Monticello is an excellent, eloquently written, thoroughly researched, convincing (perhaps over-argued), and although rightly often quietly indignant and even angry (under control), judicious and yes balanced (sigh) book. It’s as much about slavery and the beginnings of US cultural life in the 18th century, the early colonization of Virginia, the life of Jefferson’s class of people as about members of the Jefferson, Wayles and Hemings kin. The name Hemings honors (as did her children), Elizabeth or Betty Hemings, the woman who was the mother of (at least) 4 wholly African children by a black man, 6 mulatto (as they were called) by John Wayles (Jefferson’s father-in-law) and 2 mulatto by two other white men. She is the patriarch of a large ensuing clan.

I found the book compulsive reading. It’s about American earlier history and race relations today, the origins of some of our excruciating norms and fault-lines. G-R writes eloquently & honestly, nothing falsely upbeat, bringing out fully what is often presented discreetly or not at all. Most compelling in her book were discussions of norms and social and economic circumstances limiting, making people then and now.

G-R has a complicated story to tell and carries several threads and purposes through at once, which I here separate out in order to summarize, epitomize (I will tell stories) and try to evaluate clearly. Her central problem is she must rely on too little documentary evidence, and tries to make up for this by too much speculation at length so the book occasionally becomes repetitive.

She tells of how slavery came to be institutionalized. It was not necessarily in the cards that the western hemisphere would be taken over to make money and grab land and found families on the basis of slavery. Indeed the British driving the French Acadians so brutally from Canada wanted to have non-slave labor in Nova Scotia. But it was too tempting to get someone for free and there was a long tradition before of slavery in the world (seen as mitigation of war — after all the person was not just murdered or as a woman raped and abused until she died), plus in Africa the very bad land for growing (two huge deserts) made it more economical and profitable for African tribes to go to war, enslave the losers and sell them.

The Western Hemisphere set up a different basis for slavery by using race as the central marker of the person who would be enslaved for life. To use the color of someone’s skin was to use a visible marker. Early on then there arose the problem of what happens when a white man fathers a child on a black woman. Is her child a slave? People went to court (black people who hired lawyers too) and those arguing not lost quickly because Roman law was used: that said that if the woman was a slave, her child was a slave in perpetuity. The law favored men having sex when they wanted and other men not losing their property by this. That was a bad day for black people and black women. The difference that one was a slave forever unless you could buy yourself out was the main different between indentured servants who were white and early on every effort was made to allow poor whites to despise and exploit black slaves.

To understand what happened to the Hemings as a result of being literally owned by by white people is the whites did all they could to deprive them of personhood. I own three books on and by Jefferson: Adrienne Koch, ed., introd., Life and selected Writings of Jefferson, Vol 5 of Jefferson the President (on his second term, 1805-9) by Dumas Malone, and Jefferson in Love (the lover letters of Jefferson and Maria Cosway), ed, introd. John P. Kaminksy. In each Jefferson is treated with unqualified respect. We are told of his humanity towards others, his compassionate respect, originality of thought, decency, his real strength of character. In only one (Kaminsky) are his slaves mentioned; in none is justice done to the centrality of his relationship with them.

Jefferson was humanly speaking their brother-in-law (through his first wife), uncle, cousin, of Elizabeth Hemings’ children and grandchildren, the father of 5 children by Sarah (Sally) Hemings. He kept all these people near him, educated the men to be skilled tradespeople, freed his cohort when he felt he had his his moneys’ worth of training them or at the end of his life (after they served him utterly when he needed them with his needs given all priority); and he freed his children by age 21. Sally lived her life from age 14 next to him; was always there for him until he died; she had her own room in his private quarters, was taught to read and write (she spoke French for a while at least); was dressed respectfully, was in effect freed and given wherewithal to live with dignity upon his death. But never once did he write her name down, never once acknowledge what was his relationship with her. He was (as far as we can know) never openly loving as a father to his children by her; he rarely referred to them in writing and then always in coded language.

There is no a single picture of anyone but Isaac Jefferson, the son of Ursula Grainger, who had been Jefferson’s wife’s wetnurse. Like Madison Hemings (Jefferson’s second son by Sally) Isaac was interviewed by a reporter and the resulting writing has come down to us as their memoirs. That’s significant. Most of the people were not photographed until granted the status of people and the right to be remembered.

It will be said he protected his relatives and (in effect) friends this way; given the virulence of hateful prejudice (especially violent because the whites of this culture were so horrible in behavior to these people), he and his white family were also at risk. But never once is there a discernible gesture left of his granting them full person-hood in his eyes. G-R will write that James when freed asked to be treated with dignity and reciprocal need and was not. She suggests that John Hemings found he could not create a self-respecting life of his own after Jefferson died. That the code was never to acknowledge their existence as people around them in writing. Jefferson did clearly treat them as people but quietly, silently and without admitting it. The Hemings are to be erased, not remembered.

And in acting this way he violated something profoundly important in bringing up and interacting with them. as far as we can tell his white relatives behaved similarly. This was his searing sin as chance and his own choices — especially the taking of Sally’s life as his to have — had given him the power over them to have done more right by them.

************

A chair carved for Jefferson by John Hemings, Elizabeth’s youngest son — his poignant life story emerges late in the book

We begin with Elizabeth Hemings (1735-1807, Betty), a mulatto (to use the term used then) woman. Her mother Parthena, a black woman was impregnated by an English captain named Hemings. We know about this by a memoir; he tried to buy her and her infant (his child) out of slavery but Francis Eppes, the owner was not selling. G-R says one reason that most freed slaves found in the US were mulattoes is that often white fathers did feel something for their children and did try to educate or free them occasionally. Parthena and Betty were sold to John Wayles. It seems that Betty was very very pretty — this was important — and also smart. As far as we can tell she was always a house servant. By the time she was in her early teens she was being impregnated by black men — it’s fair to say she was being used as livestock.

John Wayles’s life, character, and economic success is put before us: he was a brutal ruthless determined man, began life in England as working class, a servant and brought to the US and rose to become a lawyer — he had enough education to put out a sign, just. We see how he finagled and the people he had to deal with. When Betty was 18, he took over her body. He had three wives of his own beyond her. His first wife was an Eppes mother of Martha, Jefferson’s wife and when she married she took these half-brothers and sister (not called that of course) into Jefferson’s household and that’s how Jefferson came to own them all.

Elizabeth Hemings is called Wayles’s concubine until he died and then joined the Jefferson family. She was not his common law wife as slaves were outside the law; she did not (as her daughter did) live as a hidden substitute for a wife either. The norm then was to pretend white men didn’t take black women to bed with them as a regular thing. No one discussed it and it was done privately — at night, or discreetly. Jefferson differed in that he didn’t hide Sally in the way others did; at the same time he never wrote down anywhere that Sally was in effect a wife, her children were his & Elizabeth’s were related to his wife as half-siblings. This was part of the code.

The code was to erase black people. They didn’t matter. Who and what they were didn’t count. I see this as relevant to the way class and illegitimacy works today. We — many of us — many have come across cases of illegitimacy where no one writes it down and no one admits to it, sometimes where the child has as a father a kind of cover, the mother’s husband. Socially, as social knowledge, everyone knows who the father is (by time, circumstances, resemblances), but by not admitting to the reality you can hide behind the protections of legal fiction. It also renders powerless the woman involved (white too); the only person who deserves protection will be the biological father and the legal one.

What G-D’s research did was break through this code. She was aided by Jefferson who again did treat the Hemingses differently than his other slaves, not like free people, and not like his legitimate daughters and sons-in-law: whites inherited your property, were your companions in public social life. Black people were unacknowledged intimate companions whom Jefferson rewarded with education and skills and minimum coercion (he expected the system to do that for him). Some white fathers did treat their biological children more decently (like Jefferson) but since records are so sparse even for him(we are dependent on his farm books, these reinforced at long last by DNA studies), it’s very difficult to find instances to study in detail. That’s why the Jefferson and Hemingses are such a gold mine.

I want to stress the class bias too. Wayles was originally a servant who became a lawyer; I said he rose by force of brutal personality, by intelligence and luck. Again and again we see that he was quietly despised by those Virginians who arrived earlier and came from gentry in England. He defended a man, John Chiswell, accused of killing Robert Routledge during a quarrel in a Williamsburg tavern. Snide references to Wayles abound; he is forthright in his own defense; the business was brought to a halt when Chiswell killed himself but the documents show the class side of these world. Very like ours.

When Wayles died, it was against the law in Virginia to free slaves except in cases of “considerable merit” and the standard was high and had to be approved by a governor and council. If you tried to free the negro, the churchwardens of a parish could try to snatch the person and put him or her back into slavery. That’s interesting: it suggests some people did want to end slavery and free their slaves. To do so remember meant depriving your children of considerable amounts of property and people really do want to leave their children what they can. Here she does not mention buying your freedom.

****************

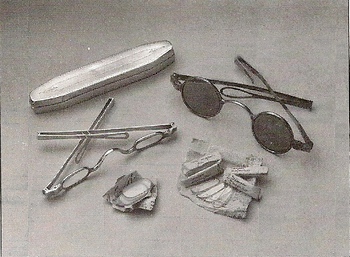

Items Jefferson carried in his pocket

When Jefferson enters the picture, G-D takes time out to give his story. Kierner told too little of Jefferson. It’s important to know his mother was a Randolph. In Virginia this family is still not gone from high social life. We have Randolph-Macon college and Randolph college in mid-Virginia. Jane Randolph was Jefferson’s mother. It’s been said he didn’t love her, or was cold somehow towards her since few papers by him about her survive. G-D suggests they could have gone in a fire, but it is true he was far closer to his father. He was early on recognized as highly intelligent, capable. and educated accordingly. He was close to a sister, Jane. We are told of the men who became his mentors and his patrons and how they pushed him forward. How they knew Wayles from courtrooms and thus Jefferson meet Martha. He was very creative, loved to do mechanics, liked working with his hands, an architect himself and builder. He educated his sons, Beverley, Madison and Eston (by Sally) under the tutelage of of their uncle John Hemings (Elizabeth’s son) to be carpenters. Jefferson would walk round with a compass and other gadgets in his pockets. He read enormously,very verbal, loved music — as did his first wife.

Jefferson was ambitious and from his early days we see a radical thinker. He lost a case because he offended a judge. Samuel Howell brought suit to be freed from indentured servitude. As a punishment for having a child out of wedlock by a black man (get this), Howell’s white grandmother was fined and her child (Howell’s mother) was born out for servitude for 31 years (an average life span); Howell was born during this mother’s servitude. Jefferson worked with extreme diligence to search for any legal precedence or theory that might aid him. His brief included these words; “all men are born free and everyone comes into the world with a right to his person and to use it at his will. This is what is called personal liberty and is given him by the author of nature because it is necessary for his own sustenance.” We are not far from “inalienable rights” here. The judge cut him off in mid-sentence and the man lost the case. Jefferson gave Howell money and soon after Howell ran away and was never heard of again in that area of the US. On the legislation punishing women for having sex with someone of the other race, Jefferson wrote these strictures were to “deter women from the confusion of species which the legislature seems to have considered an evil.” Seems to have is a strongly sceptical note here. (pp. 100-1)

Before he married Jefferson wanted to life his status, and that’s why he began the first Monticello. He and Martha lived on the site in a small house, a sort of one gigantic room where they did everything. It’s apparent that they socialized and networked from the very beginning even in these small quarters. That’s why they needed servants. This house meant a lot to him, so too did spending money and living well. (Thus the later debts.) He did just love Paris and the time he spent there.

Jefferson did quickly single out Elizabeth’s sons (his wife’s half-brothers), Martin (by a black father), Robert and James to travel about, learn trades, hire themselves out and keep their money. He freed Robert and James during their lifetime – they were Sally’s close brothers. He freed all his children by Sally as young adults so they had their lives ahead of them. Three others he freed (more distantly related to him or them) he freed when they were older – and had “earned” it.

He treated black women as feminine, which by his standards means they were not to work in the field and do hard labor. They were house servants and encouraged to dress nice, ornament themselves — like white women. But since they were slaves, the real result of this was they ended up being sex partners of the men in the house. The place was rather like a stereotypical new Orleans: white males pursuing and attaching themselves to light-skinned black women. The norm for black women slaves was to refuse to recognize their ‘femininity” as European standards saw this — so you could work them hard in the fields, endlessly impregnate them and demand they get up and work the next day or so, sell their children and them at will. Jefferson remarked on European peasants how shocking it was that women worked in the fields. In Africa women worked in the ground too. But of course these women were not slaves, not subject to rape.

There is much sympathy for whoever is the underdog throughout. G-R does make us aware of how much his white wife Martha suffered from these yearly pregnancies and how she didn’t have to die at 35

It was a great grief to Jefferson and he really collapsed over it, went into weeks of depressive behavior – stayed alone, couldn’t sleep, would talk to himself. Partly he knew he was partly responsible for her death, since it was he who kept impregnating her. As she lay dying, she asked him not to remarry so as to not put another stepmother in charge of her two girls. This suggests her father’s second and third wives had not been good experiences. He didn’t remarry. Perhaps like Edward Austen and others I’ve come across Jefferson couldn’t see his way to use some form of contraception (other practices beyond full frontal intercourse were known and among others, used by Fanny and Alexandre d’Arblay) or keep away or control himself or treat his wife other than as someone he must use sexually to the full.

Jefferson had also suffered badly as governor. He had been unable to cope with the military part of his office (perhaps partly because he and Washington did not have sufficient funds to cover all the areas they had to) and was for decades afterwards harshly criticized for not using local military to fight Cornwallis in Virginia. When he didn’t, Richmond and then Charlottesville fell to the British and he had to flee and his family too. He had wanted to retire before this — again not understood at all by people of this generation, especially other men. These bouts of retirement recurred after the first wife’s death so they were not just the result of wanting to be with her and his family (his rationale).

G-R tells of how the Hemingses experienced the American revolution. She has some memoirs, oral traditions, and some papers Jefferson kept too, and a later interview of a great-grandson of the Hemingses’ Among other things, when Jefferson fled he left the house in the care of Martin, Elizabeth Hemingses’ oldest son by an unnamed black man. Martin stood up to Cornwallis and would not tell where Jefferson was at threat of death. This is sometimes interpreted as see the loyal black slave. It was actually in his nature, unflinching and aggressive and the kind of person who would rise to be the one in charge were he not have been enslaved. There’s one of this hide the treasures stories. Martin hid Jefferson’s silver and as the soldiers were coming in could not let another black man out in time so Caesar had to stay below for a couple of days and nights.

We see Robert and James, Elizabeth’s sons by the white Wayles, accompanying Jefferson and how they were educated.

Finally Elizabeth and her daughters did the work of the house and were the people who cared for the wife as she lay dying, the hard work of all this. They are never mentioned in white accounts as if they weren’t there, as if Martha did the work. No she ordered them to and probably didn’t closely supervise .That was Elizabeth’s job.. G-D tells of how (ironically/) Martha the white wife signaled out Sally before she died to give Sally a hand-bell as a memento. An ambiguous thing to us as it was this hand-bell Martha used to call Sally by. It does show a particular regard.

***********************

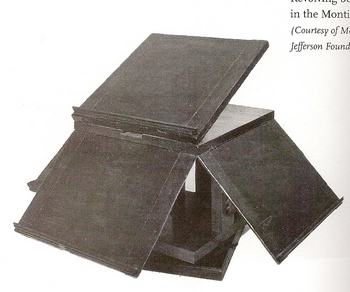

Revolving bookstand made in Monticello Joinery in later years

James Hemings, a Provincial Abroad (in Paris)

Not Jefferson, not Patsy his daughter. I’ve not mentioned that one real obstacle G-D has is lack of documentation. So in this chapter where she builds a picture of James’s life in Paris, 1783-87 (and beyond when Sally and Polly arrived, and Jefferson was having his affair with Maria Cosway and Patsy living at the convent still), she has to theorize and use what is known about black people in France in general in this era. (I had to do the same for Anne Finch in my chapter on her girlhood; I talked about what was done usually, what was done in the place and schools she might have gone to.). She suggests that James bought the cloth or clothes for clothes-making. She suggests it was an eye-opener to James to see Jefferson and his daughter outfitting themselves. They had been the high ideal in Virginia. The house probably startled him – and the varied interesting company (which dazzled Jefferson and he loved it.) She tells a couple of stories of other black people that have come into the records and documents, for example John Bologne, Le Chevalier St-George (circa 1745-1799), sometimes called “the black Mozart” (about whom I had heard a talk in an EC/ASECS conference at Penn State).

G-D succeeds in persuading us James Hemings had an almost equivalent experience of a white young man who goes on a grand tour. His eyes were opened, his experience enormously widened. His letters of introduction were the apprentice papers that took him to several palaces and several chief French chiefs. He had freedom of movement; Jefferson paid for “all found” (daily food, his lodging in Hotel of course, his clothes). The rest was his.

Did he have free movement? The trouble was racism even in France but this in conflict with “the freedom principle.” Some people wanted to keep blacks out of France (much fewer than in England, some 4-5,000 out of 30 million while in the UK it was 10,-20,000 out of 9 million) and others wanted to free them. The law demanded Jefferson register James’s presence; if James stayed more than 3 years, he was automatically freed. Jefferson got round that by not registering James and we have notes in his handwriting advising others to do the same.

But he did not need an escort of an older white person around as he had in Virginia. No one would beat him up, no one snatch him. Yet the one note we have beyond the apprenticeship noted in Jefferson’s diary is Jefferson’s note sent indirectly to James’s mother: “James is well. He has forgot how to speak English, and has not yet learnt to speak French.” A light kindly joke.

Jefferson’s spectacles and other items Sally kept and handed on to her children

Sally at the Hotel de Langea

Annette G-D says Jefferson did not want Sally to bring Polly; he wanted an older woman. Thus we cannot say he was looking to bring a concubine to Paris for himself. But once he came, that is what G-D thinks he after a little time made Sally into. Inoculated against small pox, while his daughters had typhus, put to stay with a friend she was apparently given nothing to do. G-R says the unusual thing about Sally is she’s never mentioned with any concreteness. He quarrels with Martin, comments on James, sends directives to just about every Hemings but Sally. She is suggestively in one place only said to be his “female chambermaid.” There’s the negative response of Abigail Adams: upon seeing the girl, she urged Jefferson to send her home as not of use, as a little non-effective or puzzling a a 16 year old too old. Abigail thought her 16; she was 14.

So Sally was taken in for the next four decades as Jefferson’s mistress. There are signs she was given French lessons and there are orders for very nice cloth for her. At another point she seems to be included in a group of servants sewing. Women sewed. She did stay in the house most of the time. She was not registered as a slave and this way he could keep her beyond the 3 years without having to worry she’d be free. The convent he put his daughters in freed slaves left there. Keeping them in the convent was also convenient for keeping them out of the way.

He has already begun his dalliance with Maria Cosway and their apparently famous correspondence has begun. I saw a copy of the letters for $1 so I’ll be reading that slender book soon.

For Sally we may postulate she spent time with James down in the kitchen, that she saw and enjoyed what was available through windows. Her life circumscribed like that of her half-nieces, Patsy and Polly. I am struck by the use of euphemism for her in later accounts (which G-R uses): they remind me of the way Eliza Austen’s mother, Philadelphia Austen is discussed as well as the probable illegitimacy of Eliza. Gender makes all women one when the male is powerful and gentry educated.

she does seem to have gotten an allowance — like James. Disposable income. When Jefferson did not need her, she was free to wander about — had to be careful that’s all mainly because she was not registered. (Had no papers you see). (My own comment: there is no record of hats made; I wish there had been.) Oral tradition in Hemings family was she talked of Paris to her dying day; made a huge impression, perhaps like Jefferson himself a very happy time for her. We may even imagine them coming together if not in love as not equals, but both having this good time, older man, younger girl, after all movie not so wrong

***********************

Thomas, James, Sally and Patsy go home

Jeffferson returned to the US thinking he would return soon; he was asked to be Washington’s secretary of state and he could not turn that down — if only for the sakes of others who were attached to him. He also persuaded James and Sally to return with him. Martha was thwarted in love and went perhaps expecting a continued debutante life. Her father married her off within 2 months, to the son of a friend.

She persuades me that the explanation for Sally going home when she could have been freed, and in the paragraph pointed this out to Jefferson, is the relationship was one of trust, affection, and satisfying to both, very much. She had not been raped, though her position shows she could not easily have said no. Once there he treated her very differently than just about all known relationships of white masters and black concubines: she was set up in Monticello, in the house, in the central quarters and lived there (one stray remarks shows this. When there was another illness, she was not called upon to nurse (that’s the second stray phrase). He depended upon her to be there; he wanted her the way a man wants a stay-at-home wife who he is congenial with and comes home to rest by. There are such relationships.

G-R also tells by contrast of terrible relationships: one Celia, age 14 also, this one a rape by a master, put in a cabin of sorts, and raped regularly until she murdered him, burnt his body, and gave the ashes to a grandson. We know about this because there was a court case and interestingly her side was told (by an abolitionist leaning lawyer). She was hung.

She tells of ordinary ones we can track — the white woman kept away or made to work with the other slaves, even if her children were treated better or eventually freed. Very common the older man taking the pubescent girl.

And she tells of Jefferson’s white women. His daughter married off at not quite 17. Now we are told more frankly of Martha’s husband’s violence, and how he came to be over-shone by Jefferson and Martha as much Jefferson’s non-sexual wife as he was Thomas Mann Randolph’s sexual one. Even if they didn’t get along after a short time, her life was one of yearly pregnancies. The girl Nancy shifted over young to a Randolph branch who became the mistress of Randolph’s cousin and the infanticide. Especially the brutality of Martha’s oldest daughter, Anne’s husband, how he beat her and impregnated her to death and nothing much done to stop him. Anne too married off at 16. G-R quotes Kierner to the effect that Martha, Jefferson’s daughter did after that one marry her daughters off much later — or not at all. The non-marrying becomes almost a deliberate choice or option for Martha’s daughters (though at the end they did have to open a school).

*********

With Sally settled into Monticello, Thomas Jefferson is off to New York with her brothers. He is going to be secretary of State to Washington and takes up residence a couple of blocks away from Washington. Their long journey in the snow by carriage. Robert has been spending a lot of time away from his “master” and continues to be given “general passes” (which were frowned on by other whites). He had married a woman named Dolly while Jefferson was in Paris and shortly after they arrive in NY he leaves to visit her. He never asked Jefferson to buy her as Jefferson did buy the spouses of other slaves. He apparently preferred to keep her and his life apart, and he pretty quickly also began to hire himself out. He seems to have led a remarkably independent life — for a slave.

He never ran away. Jefferson’s rule was to sell all slaves who ran away and could be brought back. Not before flogging them harshly and telling the person who bought them not to keep them beyond immediate need but sell again. Not kindly there, was he?

James settled down to being chef. In the film Jefferson’s attitude is voiced: he felt that James owed him a couple of years of being a chef and to train others before he freed him. He was again given an allowance. Both NYC and Philadelphia were places where the nature of liberty and freedom were part of life and ardent discourse. NYC had a sizable number of black people, some free. The talk was a spillover of the French revolution going on just now — as well as reaction to what was happening in England (strong repressive measures as well as war and depression).

Jefferson also began to have usual illnesses, psychological in origin these, migraines. James is mentioned each and every day of the diary; it was he who went and got Jefferson his medicine. She makes the point that James and Sally Hemings probably knew Jefferson intimately as well perhaps better than anyone else.

High Street, Philadelphia, 1799: James lived on this street in the 1790s

But soon the capital was moved to Philadelphia and so Jefferson and now 4 servants (2 non slaves) moved there. He felt he was going to be permanent enough so Jefferson never seems to have moved anywhere without full scale renovation. He began this – always the big library and something like 89 boxes of books. (I begin to identify though not with the renovation and moving.)

***************

G-R presents a much more positive view of Jefferson than she could have; her purpose was to persuade as many readers as possible to take an interest in, respect the lives of the Hemingses and that’s served best by judiciousness.

In Paris, there are often conflicts between servants and also would be between slaves and servants and from some of these emerge information and insight into James Hemings’s life — because white people left documents. One French servant’s wife, Seche, alleged another indulged in “sodomy” and that he loved men. Petit demanded Seche’s wife get out. Since Jefferson’s longer relationship was with Petit, and he needed Petit’s services, more the Seches had to leave. We have a letter from Jefferson showing him using a confidential direct personal note with Petit. Petit refers in a letter back to “Gimme” (James) and “Salait” (Sally). Jefferson did not hing about this taboo behavior — as he never appeared to try to punish or ostracize his son-in-law’s sister, Nancy when her brother-in-law impregnated her and participated in an infanticide.

This keeping his cool is characteristic of Jefferson. There exists a correspondence from these years between a black free man, Benjamin Banneker, from Maryland; Banneker presents an almanac to Jefferson who write back with great respect and sends the almanac to Condorcet and then helps Banneket get a place (job) as an assistant in surveying land for the Federal District (p. 475). This was going beyond just courtesy and helping quietly.

Now 18 years later it was charged that Jefferson helped Banneker in his superior almanac and then became a target of those who hated his support for the French revolution, his mild anti-slavery and when Banneker and his friends printed Jefferson’s correspondence with this man, Jefferson simply kept quiet about it (p 477)

G-R suggests at the time of the original correspondence Jefferson might have told James Hemings about it.

Jefferson had no problem in offering common courtesies to black people in public. He once rebuked a grandchild for not bowing back to a black man who bowed to them in the streets (p 477). He referred to servants as Mrs, so Henrietta a washerwoman was called Mrs Gardiner , p 479. Things like this count. A lot. There’s a stray remark by someone later on (oral tradition) that Sally had her own room apart from Jefferson at Monticello. Her own space.

I’ve been snubbed and know how much it hurts. I can’t bear when someone calls me by my last name without the title; it’s disrespectful, abrasive. It would’ve cost so little to the person doing the snubbing is what I keep my eyes on. But to have given her a room of her own goes beyond this.

The story of how the three black men who were so close to Jefferson finally left him — were freed – is ambiguous too. The chapter is called Exodus (the allusion to the Bible). Mary, Elizabeth Hemings’s oldest daughter by a black man was sold to Colonel Bell, the white man who had become her substitute husband. Jefferson believed all women ought to be under the control of a white man. But he only sold with her her younger children; he did let all her family go, her “older” children, including Joseph Fossert then 12 and his sister, Betsy, 9, stayed on as slaves. Joseph was a talented artisan. To understand this takes a lot of trouble since the language used to describe it in the letter is so coded.

Elizabeth’s oldest son, Martin, called “the fierce son of Betty Hemings” by Lucy Stanton (a later reporter), the man who held Jefferson’s house together while Jefferson fled during his time as governor during the revolution, quarrel, and Jefferson writes that he will sell Martin at Martin’s request to a man Martin approves of — Jefferson’s tone is of one furious. In another note (earlier the selling of Martin is referred to as the equivalent of selling a chariot). But in fact this did not happen (tempers cooled?), Martin stayed on in Monticello for 2 months and then went to NYC (or DC). He was quietly freed and heard of no more in the documents.

The second son, Robert was just as bad. When the quarrel occurs Jefferson says James is “abandoning” him. It’s been told that a deal was worked out where Robert’s wife’s owner bought Robert and then Robert from his saving re-pay Stras and thus be free. Again Jefferson felt this was somehow dumped on him unexpectedly; that he had expected more years of services, and you see hurt and anger. A kind of bitter lament referring to what he had taught Robert (including barbering). Jefferson thought one could build emotional capital with a slave but he does not realize at no point can Robert really assert his identity or what he is or choose freely. All is given and he is to be grateful; much is demanded and he to be quiet.

A tense struggle occurred at the end of Jefferson’s time with James show Jefferson expecting reciprocation from James and (like many powerful people who are higher than you say) not understanding how James must’ve seen the relationship. Jefferson’s notes about James have phrases like his “desiring to befriend” James. Jefferson wants James to stay on as cook after they go home from Philadelphia after the ordeal of his time as secretary of state.

Elizabeth’s youngest daughter, much younger than any of the others is sold to James Munroe.

Elizabeth herself retired to a cottage much as Sally did at the end of her life. It was an arrangement which freed her in fact but where the Jefferson carried on paying her expenses and protecting her from “snatching.”

The analogy G-R uses much earlier is a propos: Baldwin says that when someone would give him a small version of what Baldwin felt others (whites) got much bigger how it embittered him; it was not a reconciler. I understand that too. You are not grateful. G-R “they did not want to give their very lives to him any more than he would have wanted to give his life to them.” The shows of devotion while slaves are not to be taken at face value and Jefferson could not understand this. He was also unusually powerful and respected and they knew this. He could and would help him. but to be with him was “emasculating” too says G-R — as it was for Martha’s husband, the son-in-law.

The one person who did not leave was Sally. Her decision to return to France permanently fixed her in his orbit until he died.

Poplar Forest, Jefferson’s other plantation, a retreat for all, black and white, late in Jefferson’s life

Continued in comments.

Ellen

When Jefferson returns to Monticello — considerably scathed by his time as Secretary of State to Washington and begins to renovate and rebuild Monicello, we learn about Elizabeth’s cabin on the estate. 170 square feet. It’s typical size for a woman slave alone. Archeaologists have dug there and discovered some of what she owned, how she lived – – quietly, meagerly, using things from the great house.

Peter her son who James taught to be a chief is declared by Jefferson in his diary to be highly intelligent, very capable. Elizabeth herself begins to visit the great house again. Although Jefferson gone a good deal between 1790 and 1794 he’s there enough to impregnate Sally again and within 9 months of his first night staying there Sally gives birth to their first son, William Beverley. Again, Imagine being Sally. I can’t.

Meanwhile other documents about the freed males are usually by Jefferson. Try hard as they can, they have to turn to him. An interesting note by Robert – -who remains in Richmond possibly because he is known as connected to Jefferson — “a present from Mr Hemings”. This in response to a request by Jefferson for some of the juice Robert peddled. Robert became a peddler. Robert would not accept payment you see. Note the pride.

James went traveling, Philadelphia, around the US and overseas — we don’t know where exactly. Perhaps Spain. Surely France – where James spoke and wrote French. Jefferson again drawn from a retirement, now to be Adam’s vice-president, is in Philadelphia and meets with James so we have a note to his Jefferson’s younger daughter, Maria (aka Polly): “James is returned to this place, and is not given up to drink as I had before been informed. He tells me his next trip will be to Spain. I am afraid his journeys will end in the moon. I have endeavored to persuade him to stay where he is and lay up money.”

Laughable in a way: Jefferson telling James to lay up money. G-R says a theme that emerges from the little we know about black men freed before the Civil War is they are said to travel too much and drink too much. How could they easily settle? They’d be outsiders. With their freedom surely they wanted to roam far and wide. It is said to be true that male cooks in this era tended to drink heavily. I like G-R’s sensible idea that because a person drinks or even drinks heavily that does not mean he or she is a alcoholic. How refreshing she often is.

Jefferson returned home briefly where he could have been seeing his first son by Sally.

E.M.

I am here reducing many pages of reflections, suppositions, all built out of a very few documents and stray comments here and there, and much thought about what the meaning of the coded exchanges is.

We see how slavery wreaks havoc on all familial arrangements. Let off this snapshot: By 1806: from records in farm book we know that Sally had had 5 livebirths, 2 children died, 3 then living: Beverly 8, Harriet, 5, and Madison nearly 2. The last of Sally and Tom’s (so to speak) babies was born: Esten. So the couple had 4 children. In that year Jefferson was 63, Sally 35. Records indicate that whenever he came home he immediately began a full sex life with Sally as often she would give birth after a visit that lasted a short time just nine months before. Jefferson’s oldest white daughter was 34 and his younger one, Maria, had died the year before. All grandparents were dead but Elizabeth Hemings who died the next year. A family of 5 children were what Jefferson had plus grandchildren from Martha and Maria, some of the grandchildren older than his and Sally’s children.

Madison reported years later that although was “kind” to Sally’s children, he was not “in the habit” of showing “Partiality or fatherly affection” to them. G-R says there are records he did show that to his white grandchildren. Madison was clearly a bright man and along with Isaac Jefferson left some perceptive remarks. For example, Madison says that Jefferson was one who did not allow himself to become unhappy for any great length of time and if made angry or disquieted, he would forgive the person as far as he could and the dismiss the incident from his mind. (Madison did not see the younger Jefferson who went into paroxsyms of grief over his first wife’s death.) (p. 374).

You don’t see this at all from the records but must work it out.

G-R tells the story of James’s suicide. It was preceded by an attempt by Jefferson to lure James into becoming the cook at the White House. In the letters it’s clear that James wanted some show of affection or deference or need for his services and that Jefferson refused to show this. James wanted to be treated with dignity, to be for example asked directly. Jefferson then said he assumed that James preferred Baltimore suggesting possibly some attachment, for he Jefferson could not imagine James would not want to come to work for him. And Jefferson hired someone else in his place. That summer of 1801 we find James is cook again at Monticello so there was no break (p. 349). But to return to the mountain as a free man surrounded by the old slave system with Jefferson in place as usual could not be satisfying. James left September 1801 and by the end of October or early November Jefferson hears through some grapevine of James’s “tragical end.” Apparently we don’t know how James killed himself.

White and pro-slavery advocates have used Jame’s suicide and supposed alcoholism (we don’t know that he was an alcoholic at all, just have one comment by Jefferson that “James was not into drinking” any more as much as Jefferson had been told James was) to demonstrate how one could not free slaves because they lacked courage to live, were not responsible; see you fee him and he self-destructs. Rather he could not find a place for himself to be himself nor find any deep attachment he needed (p. 552). Jefferson withheld it.

It was right after Jefferson became president that the exposure of his long-term relationship (which was what was so offensive) became known and the target of harsh derision. An man whom Jefferson had been allied with as radical types, James Callender, who became very angry when he was put into jail under the Alien and Sedition Acts (so you see in Adams’s adminitsration the same kind of thing we see happening in Bush and now Obama’s administrations through the use of the Patriot Act happened). Callender served his term until Jefferson became president whereupon Jefferson pardoned them all, and had his son-in-law give back the fine of $200. Randolph hesitated (ever broke) and Callendar became infurtated. Callendar also felt he had not been sufficiently helped by Jefferson. Specifically he wanted the job of postmaster general and Jefferson would not give it to him. He was the first to reveal and keep up the polemic; he was genuinely horrified that Jefferson a white man could have and keep a black mistress. (p.555- 558) Callender got some things wrong (such as Sally had 5 living children, no she had given birth 5 times).

John Quincy Adams’s super-snobbish wife was also deeply offended by this relationship. While Sally never lived in the White House there is some reason to believe she did visit (!). At one point when Jefferson agreed to see a delegation of Native (Indian) women and have them to dinner at the White house as part of his willingness to negotiate with Native people and at least seem to be making concessions (if he intended to he may have been thwarted), Louisa Adams is said to have burst out next we’ll be having “the incomparable Sally” at the table with us. Incomparable. A bitter but revealing word.

I’ve little stories I’ve culled out to tell. First 2 striking telling anecdotes from this part of the book: during the time Jefferson was president. These are about inheritance in this era, an intensely fraught subject in ours still, but far worse then because there were so few ways one could rise or get money or property but through family and friend connections.

In one case quiet acceptance of a white man leaving much or all of his property to his black family. When Colonel Thomas Bell died he freed Mary and their two living children and left his property to them. Earlier she had had a chance to be freed, but did not take because at the time she would not have been able to take all of her children with her. Now there were but two living. There was no white family to protest (pp. 572, 595)

In the second a white grandson murders his white grandfather and the grandfather’s black heir, a son. In 1806 Jefferson’s law teacher, mentor, friend, George Wythe was murdered by his white grandson, George Sweeney. Wythe had been married twice but had no living direct children. Wythe then left his house and property to a free woman of color, his (supposed) housekeeper, Lydia Broadnax. He also left property to Benjamin, another freed slave, and to Michael Brown, a 15 year old African-American “ward” whose finances and education Wythe asked Jefferson to take charge of. Sweeney managed to poison the boy to death. Sometime later Lydia Broadnax wrote Jefferson in dire need of funds and Jefferson sent her $50 a big sum in those days. It is not said whether Sweeney was punished for his crime, nor if Broadnax did not get the property she was supposed to. We have only a statement written by Jefferson how much he missed Wythe and how he regretted Michael’s death because it “deprived him of an object for the attentions which would have gratified him unceasingly with the constant recollections and execution of the wishes of his friend” (p. 592). It seems a fair assumption that Michael Brown was Wythe’s son, probably by Lydia Broadnax.

Here is another close friend of Jefferson also with a black family.

Then two showing Jefferson trying to deal with the occasional horrific violence even his plantation fostered and his using young man at hard work from which they could have no aspiration away (Rather like Dickens in his blackpot factory). A brutal man, Gabriel Lilly was hired as overseer for this nail factory Jefferson subjected his black male slaves to. One day James, a son of Critta Hemings, grandson to Elizabeth fell ill and Lilly beat him so mercilessly he was sick for 3 nights and days. When he could not work, he begged Lilly not to beat him again, but he began to whip James 3 times a day. He could not raise his hand to his head. Well he ran away, probably to Robert Hemings in Richmond. Jefferson did not fire Lilly right away and he wrote down a note about “readily excusing the follies of a boy” (!); from the records it seems that James was bought back but if you pay attention you discover that not only did James never return, but within 2 years there are no records of him. Probably he was given his freedom and fled the south (pp. 577-78). Lilly had gone too far from Jefferson’s point of view and was only eventually fired, violated some human reality — but we find in Bailyn’s accounts of life in the US at the time (The Peopling of North America) such supposed every day tolerated horrific incidents of such behavior (terrible beatings daily, nightly, forcing people to drink piss, putting irons in their mouths) that Jefferson not making any public stand even in his own house on behalf of his boy is reprehensible.

To say that Jefferson avoided confrontation (as G-R does) will not do.

In another case one enslaved man, Brown Colbert (related to the Hemings), was teasing Cary, another young black slave, and Cary attacked Colbert with a hammer. Cary so broke Colbert’s skull an operation had to be performed to remove some of the skull bits from Colbert’s brain. The attack “made Jefferson livid” and he is on record about it; “It will be necessary for me to make an example in terrorem to others in order to maintain the policy so necessary to nail boys.” That is what is quoted. Probably Jefferson was right to remove this boy from hurting the others, but we can see the conditions in the factory may have been humiliating, hard work, and Cary wanted to get at really those who set up the system and couldn’t (p. 578). Again quietly Colbert is freed.

Two years later a note from Brown Colbert asking to be sold to live with a wife owned by another owner, but the record shows he went to Liberia where he perished along with the other black people who tried this out (p. 580).

Finally one showing how Jefferson like so many white people simply never entered into the lives of slaves or their feelings as people for real. He could not see that James needed overt reassurance and to be treated with dignity. Here he cannot understand how a young man can try to escape the regime. Joseph Fossett one of Mary Hemings’s children, again a denizen of this nail factory is known to have run away supposedly out of no cause. Jefferson sent a slave catcher to bring him back and could again think only that Fosssett wanted to be with his wife (who lived elsewhere) (pp. 572-74) This occurred in the blacksmith shop under the control of William Stewart said to be very talented but “weird” — later G-R says he drank a lot and sang. Joseph is said to have missed Edith, the wife. But Jefferson never concludes he did not want to be a slave there.

Another really gifted young man of this later generation, John Hemings was trained and became a good carpenter (p. 379). We know about this because Jefferson wrote about him as “Johnny” albeit in super brief but affecionate terms.

It was Johnny who cared for and traveled with Jefferson’s black sons always referred to as Johnny’s “aids” or “assistants.” I’m glad to report John Hemings was one of those who was freed when Jefferson died. He had had to give up much of his life as he was born in 1776 and Jefferson died in 1826.

For slaves the worst tragedy a dreaded event was the death of their owner. For the Hemingses including those Jefferson had promised to free, this held true. Jefferson’s bankrupt state was known to some extent: as in Kierner’s book on Martha, Martha’s son, TJ’s grandson, the one who was such a disappointment as a boy, anything but intellectual and sensitive, had been trying to save the family from extinction for some time. And upon Jefferson’s death he was as determined (he had had nothing against beating a slave to work) as ever, and many of Jefferson’s slaves were sold off, and that included a number of the more distant Hemings connections, especially those called Fossett, Joseph Fossett’s children by Edith Hern. Joseph was Mary Hemings’s son, Elizabeth’s grandson, Sally’s half-brother. Among others, the 12 year old Peter went on the block. Auctioned off.

There was an attempt to retrieve the situation when they could — meaning both white and black family members. One finds some of the relatives (white too) buying back those who were sold at a later time, but some of the people were just lost — three Fossett children seem just to have vanished — records were not well kept by all whites, especially when it was not to their advantage. There was especially an effort to buy back some of the Hughes’s clan: these were descendants not of blood relations, but two Grainger people of Elizabeth’s generation. Ursula Grainger had been (as I remarked earlier) a wet nurse to Martha Randolph, Jefferson’s older daughter.

Among those who literally stayed on the property until it was sold was Betty Brown, also a daughter of Elizabeth (another half-sister for Sally — they often had different fathers), with Burwell Colbert who had the keys of the property coming up periodically to see her.

Individuals hurt badly included John Hemings who I’ve mentioned before: he was in the room as was Sally when Jefferson died and began to drink heavily. He was highly intelligent and creative, but he was intensely alienated from this society he found himself in without Jefferson as a kind of barrier/father stability point, raison d’etre for him. Another of these not-nice obtuse statements of Martha about how liberty was no good for him.

Well I am not sure she had ever known real liberty such as woman have today. Her later years were just as Kierner described, going to live with daughters, trying again to re-ascend by living in a big house, failing, dying basically broke but proud.

Sally’s way of leaving and living after Jefferson’s death was a study in quietness and avoidance — rather like him. At one point she was listed in a census in Virginia together with her sons as white (1830), three years later she described herself as a free mulatto and declined to return to Africa. Her home was Charlottesville, all her relatives and friends in Virigina. She kept contact with all, including two of those passing for white about whom we know so little (Beverley and Harriet).

E.M.

G-R’s long acknowledgements section at the close of her book reveals its limitations. She thanks everyone profusely for the great and generous help; all her friends and associates titles are fully put before us. Never was a person so lucky and (were you to think this the whole story) had so few obstacles put in her path. Here she is as relentlessly upbeat, sanitized as she accuses US historians and the reading public today of being about the American revolution and early American history. Of course she wanted her book to be respected, sell, be read by those who count and thus write another. But not a word of her difficulties, the intransigence she must have encountered now and again, and this is a direct descendent of all that in historical accounts explains her lack of evidence. She herself in this follows Jefferson and Sally in their pattern of avoidance and silence.

There are important issues of scholarship at play here regarding these two books, and this new blog, calling itself “the Junto” and staffed by young early-American historians, dealt with some of them in this post:

The post is directly relevant to Ellen’s comments, and the blog worth mentioning in its own right.

-Jordan AP Fansler,