The pain now is part of the happiness then.

Dear friends and readers,

Last night meaning to read a Christmas story by Anthony Trollope, I was deterred by Amazon. Amazon strikes again. On my stoop I found one of their harassed employees had left C.W. Lewis’s A Grief Observed, and, finding the book irresistible, read it through instead of Trollope. And naturally a blog came …

Skating by Moonlight — Ladybird Advent Calendar

Someone — a Latin poet — had defined eternity as no more than this: to hold and possess the whole fullness of life in one moment, here and now, past and present and to come — last chapter of Ross Poldark, where we have just experienced a sequence of Christmas scenes

In a (to Trollopians) a notorious screed against most matter produced for Christmas, Anthony Trollope defined what he thought a work for Christmas should contain:

Nothing can be more distasteful to me than to have to give a relish of Christmas to what I write. I feel the humbug implied by the nature of the order. A Christmas story, in the proper sense, should be the ebullition of some mind anxious to instill others with a desire for Christmas religious thought or Christmas festivities, — , better yet, with Christmas charity” (from An Autobiography)

Should it be that? Trollope’s own “The Widow’s Mite” is the story by him that comes closest to this but not all the others are quite that. “Christmas at Thompson Hall” the one he produced after writing his frustrated thoughts is a story of comic anguish and strong stress in a woman trying to reach her relatives once a year from abroad on Christmas day.

What I discover is typical is a story usually set around Christmas, but it need not be (not all Trollope’s are, as for example, “Catherine Carmichael,” The Telegraph Girl,” and “Two Generals”), a story where characters are in need of kindness and show kindness, characters who forgive, reconcile or accept themselves with one another or something, but also make sudden philosophic comments appropriate to the story, who reach for some meaning.

I have a few recent Christmas movies and stories as examples, and C.W. Lewis’s A Grief Observed, a meditation on the story behind one of them, for a coda.

The last pair of lovers, the lucky Mary (Michelle Dockery) and Matthew (Dan Steevens) clutching one another wildly in front of enormous house …. (Downton Abbey, 2011)

I’ll begin with the TV “Christmas special” (two hours) I watched tonight: appropriate to Christmas eve, thought I, a “feature” or coda which ended the second season of Downton Abbey, itself set during World War One and mostly about World War One (much softened). The sequences of events, the stories, what the characters are doing are all shaped by their occurring from a few days before December 25th, until what seems to be Twelfth Night, or January 6th, at any rate some time after the 1st when we’ve just had a “servants ball.”

Has what we have just experienced been Christmasy — well, yes, as the characters have put up and decorated a tree, had two servants’s special lunches and dinners, a Christmas eve party complete with charades, went shooting, exchanged presents. But have the individual stories been imbued “with a desire for … Christmas charity.” Not altogether but there has been much forgiveness of others and the self, some growth in self-acceptance and acceptance of one’s circumstances without blaming someone else, there’s been some real selfless love enacted, and just scenes of feeling good, partly by the characters all making sacrifices (however small) to enable another character to feel better about themselves, and have a good time. There’s been regret at having done a bad deed (but the deliberately lost dog was found), and we’ve even had ghostly doing with a ouija or spirit board.

My favorite line in the two hours is Mrs Hughes’s answer to Daisy’s “Don’t you believe in spirits, then?”: “I don’t believe they play board games.”

Audrey (Carolyn Farina) at Patrick’s Cathedral with her mother (1990 Metropolitan)

Two nights ago I saw a similar effort. The way Whit Stillman appropriated Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park is to set an analogous set of characters and action in Manhattan Christmas week (starting a few days before Christmas and ending just after New Year’s Eve) in the 1990s. Metropolitan is to me a deeply appealing movie because it’s one of the few appropriations which use words from Austen (more from Emma than Mansfield Park) and mirrors some of her central ethical questionings.

We see a group of upper class twenty-year olds from very wealthy families accept among them a young man with far fewer funds (he lives on the West side, not East, takes buses and walks instead of hailing cabs); they discuss what is a good person, reject sexual harassment (and rape), worry the question of success for upper class people like themselves who have too high expectations and have never had to endure boredom, hardship or work hard as yet. The Fanny character (Audrey) rejects Lionel Trilling’s reading of Mansfield Park as egocentric, narrow-minded and domineering. (He does not like Fanny Price and says no one can; well, Audrey loves Fanny.) The characters squabble, insult, and even fight one another (to the point of toy pistols), but the stories show our favored characters ending up tolerating, understanding, controlling themselves more out of respect for others, getting a wider perspective.

I admit I respond most deeply to the filming of typical NYC scenes during Christmas week at Rockefeller Center, on TV (the burning Yule log on Channel 11), shopping, lonely crowded streets and people going to rituals. Each time I watch I cry when Audrey and her mother sing carols in St Patrick’s cathedral.

Abel (Jean-Paul Roussillon) reads Goethe to Elizabeth on Christmas Day eve (towards the end of A Christmas Tale)

Last year it became my favorite Christmas movie and still is — why I began with Arnaud Desplechin’s A Christmas Tale. A family strained for many years by an estrangement between the middle living child, Henri, who facing bankruptcy, took advantage of the father and made him liable for his debts. The family would have lost their beloved ancient spacious house and their cloth dying business gone under, but the oldest girl, Elizabeth, is a money-making playwright and paid off the debt with the proviso Henri must be excluded from the family from now on. But Junon, the mother (played by Catherine Deneuve) has leukemia, is probably dying, so all now must pull together, including a younger son, Ivan, and Sylvia, his wife. It is explicitly a story of attempted reconciliations of all sorts.

What I love about this movie is what I like so about the Downton Abbey piece and Metropolitan, only here this central characteristic is so much stronger, more in play: just about all the characters are so complex in the way of characters in a novel, and (like Rohmer and Bergmann’s movies) you can watch and re-watch and each time learn more about all the characters. A viewer probably tends to focus on Elizabeth who is so bitter and who has a good relationship with Abel, her highly intelligent reading father, but not with Paul, her son who we’d call autistic and whom she wants to put in an asylum; her husband, Claude, has little patience with the boy. Also on Henri who dislikes his mother since she dislikes him, his grief over his dead wife, and restless Jewish girlfriend. It is Henri who helps bring Paul back to himself by paying attention to Paul: Henri identifies with the boy

This time (my fourth through) I noticed Junon, the mother, had self-consciously married a man who was ugly, not of high status, because Abel is kind and competent, a protector, loyal, and that he has enabled her to spend her life keeping at a distance from everyone. Also that Simon, the best friend of Ivan, Junon and Abel’s youngest son, and Sylvia, Simon’s wife’s has been leading a depressive life, until (in this week) he and Sylvia become lovers and Abel takes him into the factory. It seems that he was a rival for Sylvia long ago and she chose (probably not wisely she sees now) Ivan. This time I noticed it is Abel who takes both Simon and Paul into the family home they all find so precious, a kind of sanctuary inside a hard industrial city. Abel is seen quietly cleaning up, always there, the mainstay those who need to, lean on. In other words, the parents as complex people began to emerge in my mind.

The Come From Away cast as puzzled passengers ….

I’ve two more, neither occur around Christmas. Briefly this past Saturday afternoon, Izzy, Laura and I saw at the Kennedy Center the extraordinary (in the depths of feeling it occasionally reached) for an group concept, Canadian musical; and astonishing (in sudden individual moments, separate soliloquies, character sketches), Come from Away. It is the upbeat story of how a large group of American planes were landed in Newfoundland, Canada, because the area had a large unused airport, and how the people living in the towns all about welcomed the people on the planes, took care of them.

It’s a story we are much in need of since the spread of hatred and fear these past few years by Trump and his regime, and others like itaround the world. I’ll content myself with a review in the New York Times. Ben Brantley explains this show and its context better than I could.

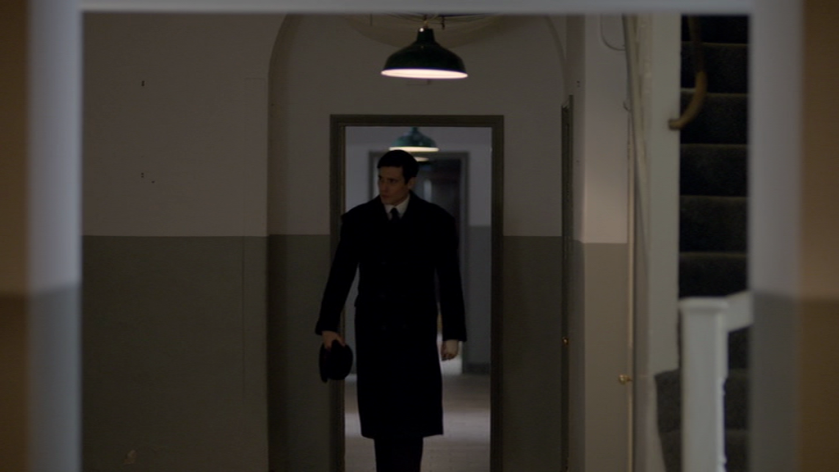

Deborah Winger and Anthony Hopkins as Joy and Jack

More at length: last week with a friend I watched Richard Attenborough’s Shadowlands, the story of the slow coming together of C.S.Lewis in his later year as a Don, with Joy Gresham, an American woman with whom he had been corresponding for years. If Christmas is mentioned, that’s because the movie covers a number of years. It does show characters behaving with singular charity and forbearance towards one another. It’s Christmasy, though, because it seeks to put the events of the story, especially a painful death of Joy Gresham (played by Deborah Winger), a relatively young woman, from bone cancer; a framework that makes it meaningful at the same time as the central character, “Jack” Lewis (played by Anthony Hopkins) cries out in anguish over the senselessness, cruel suffering and loss such a death entails. It is shaped by Christian apologetics, so to speak, especially on the existence of pain (as found in Lewis’s own writing). In the film we see Jack giving sermons on this topic.

Shadowlands was a hit the year it came out, gained many prizes. C.S. Lewis is nowadays known widely for his children’s fantasy series, Narnia Chronicles, whose stories may be allegorized as about the life and figure of Christ. I knew Lewis’s work from my 20s in graduate school as a brilliant literary critic (The Allegory of Love springs to mind), but Jim when I met him knew and was still under the spell of Lewis’s religious apologetic polemics ( which years later Jim found abhorrent): The Screwtape Letters, Mere Christianity, and Surprized by Joy, the story of his supposed conversion from atheism to Anglicanism. Maybe this is why the movie was dared and accepted.

The problem is, for some, maybe many, Lewis’s arguments can be seen as ultimately sadistic, a romancing of pain and suffering. The movie is hagiographic, follows an idealizing biography of the Gresham-Lewis relationship (with the same title): by contrast, another by Abigail Santamara tells of how Gresham pursued Lewis consciously, was very ambitious, and how Lewis was at first reluctant, married her yes to provide her with the right to live in London, and gradually fell in love. It’s a popular-oriented film so we get this reductive idea Lewis was simply cold, inhibited, in retreat, not daring risks like the figure in The Roman de la Rose (which he lectures on), and Joy brought him out of this. She is presented probably as she was — slightly obnoxious, rude in her bluntness. But the romance is very well done, the script intelligent, tasteful — the history of Joy’s cancer; the diagnosis, first radiation treatments, the remission, the return and then the decline into death is done realistically (to some extent) and made moving. We watch Lewis by Joy’s side throughout; he is there for her as she goes out — as I was when Jim died. The movie does not stop at her death but carries on, showing Lewis at first in a rage, then slowly calming down, and towards the end still with his brother and now Joy’s boy, his son growing up, if not accepting what happened, able to deal sanely with this unexpected past.

******************************

Helen Dahm Swiff (1878-1986), Silent Night

I’ll end on the book I was prompted to buy after seeing Shadowlands. It arrived today, just in time for Christmas Eve: Lewis’s A Grief Observed, yet another memoir of someone dealing with extreme grief over the loss for him or her of a beloved person, and the death and suffering that person knew. All four of these movies record deaths: in Downton Abbey, it’s the hero’s fiancee, then her father, the scullery maid and cook’s husband, son of a farmer who has lost all his children. A Christmas Tale begins with the death of the first boy of Abel and Junon, age 6; he is never forgotten during the film. In Metropolitan we are told of the death of some of the characters’ parents, the divorce of others, and one of the intelligent young men discusses what he says is everyone’s need to believe in God, and what he regards as the probably that there is a God. How else carry on? These kinds of inference I think come from over-reaching: you can see life as good and enjoy much even if it has no meaning beyond the experience of life itself. Come From Away shows awareness that thousands have just been killed in an engineered disaster.

As I began to read, I found myself remembering immediately what a wonderfully alive writer Lewis is, how eloquent, how daring his use of language. And how brilliant he is, and how persuasive he can be — partly because he tells enough truth, is so perceptive about whatever experiences he is getting down. He spoke home to me, and ranged widely. He kept several notebooks from which this slender book came. Towards the end he talks of the “arrogance in us to call frankness, fairness, and chivalry ‘masculine’ when we see them in a woman; it is arrogance in them to describe a man’s sensitiveness or tact or tenderness as ‘feminine.’ “Poor warped fragments of humanity.”

The first chapter is his own strong anger, and fear. Lewis finds grief feels like fear — yes, I felt profound terror when I first truly had the thought I would have to be alone in the world without Jim. He talks of how “it is hard to have patience with people who say, ‘There is no death’ or ‘Death doesn’t matter.’ In this first state he is an embarrassment to others; he cannot endure to listen to them. It resonated with me when Lewis says he cannot remember Joy’s face (he’s seen too many versions), hear her voice, imagine what she would say or do in this or that situation. She is now an absence. I like how he says Joy remained the other, a self apart, and when she would be with him, he would see how he had distorted her in his mind.

In the second chapter he draws himself up and realizes he has been thinking only of himself: what of her, of the pain she knew, of her loss, what happened as she experienced it. Then the cant: she is in God’s hands. Right. Will fatal disease be diagnosed in his body too? “What does it matter how this grief of mine evolves or what I do with it? what does it matter how I remember her or whether I remember her at all? None of these alternatives will either ease or aggravate her past anguish.”

The third and fourth chapter are much harder to capture. Unlike Julian Barnes’s masterly grief memoir in Levels of Life, Lewis does not move as an argument because in a way there is none: he sees the senselessness and cruelty of what has happened and then refuses to infer there is no God, and so moves in circles around the torturous draining traumatic and gradually therapeutic experiences he is enduring. He questions himself a lot. “If I had really cared, as I thought I did, about the sorrows of the world, I should not have bee so overwhelmed when my own sorrow came.” He explores what love is. We all experience “love cut short; like a dance stopped in mid-career … bereavement is a universal and integral part of our experience of love.” Then what grief: “something new to be chronicled every day. Grief is like a long valley, a winding valley where any bend may reveal a totally new landscape.”

There is much more: on God, on human consciousness, on misunderstanding less, on mystic experiences, and how he and Joy their intimacy could only reach so far. He ends with a quotation from Dante where Joy is likened (if I am not mistaken) to either Beatrice or some eternal presence and “Poi si torno all’eterna fontana.”

I hope all who read this manage a contented cheerful Winter Solstice.

Ellen