Gabrielle (Isabelle Huppert)

Jean (Pascal Greggory) (2005 Azor Gabrielle)

Dear friends and readers,

I’ve a film to recommend for those who want to understand what it is to be in a relationship (as it’s called nowadays) with someone else: to be intimately involved daily, emotionally, physically, socially, with economic and psychological dependence with someone else in all the ways we call being in a love attachment where you have promised exclusive loyalty. How people cope with the fears, demands, dangers, boredom, intriguing puzzle and inevitable mystery, and need for support is the subject of Gabrielle, Patrice Chereau and Anne-Louise Tividic’s film adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s short story, “The Return.”

It’s mesmerizing. It holds you in a kind of still fascination because of its intensity and this feeling you don’t know quite what is to happen next as both people are suddenly breaking with conventional controls or taboos (or at least we are made to feel they are) so they may break out at any moment and do something startlingly revealing, violent, scary, humiliating, touching, funny, whatever human beings can do, perhaps short of eating or killing one another. We are not scared and can watch on, do not feel we will be violated in our emotions because we don’t feel at any point they are horrifyingly violent or hate one another. They never do leave a minimum of courteous respect. And the breaking out is limited. When the two really go at one another with an intensity of traumatic feeling, what happens is they shout and physically struggle with one another to the point of messing one another’s clothes all up and crying in staccato bursts. That’s about as far as it gets. But it is enough. It is real.

Its effect depends on the norm of the film, the distanced self-control:

Stylized framed shots:

The film’s narrative: a man (he is meant to be any man in his position) has been married for 10 years. He and his wife seem to be living a comfortable contented bourgeois life. First prologue: as Jean (his name) walks home (slightly earlier than usual, finding himself in a working class crowd tightly packed in the train, on the street) we watch a mental flashback. We see his continuous successful social life with his wife, their “Thursdays,” where Gabrielle (her name) reigns as cool queen at the head of the table and the conversation with all around her and among the guests themselves is Proustian wit, soliloquys against vulgarity in the the arts (by the man who turns out to be her lover), chitchat.

He watches her

She socializes

Jean arrives and the house is quiet. He sees a note which he appears to approach with intense trepidation (shots of him coming at it from this and that angle). The note says Gabrielle is leaving him for good, has a lover. Jean loses it almost immediately and without her there begins to crack up; he then remembers himself, becomes conscious that he is making a sort of spectacle of himself (there are servants in the house) and closes the door to his room. He then he hears someone coming in. We see a veiled woman in a coat slowly climbing the stairs, and making her way into his room. His wife has returned. The text upon which Patrice Chereau (director) and Anne-Louise Trividic (writer) have based their movie is by Conrad and is called “The Return.”

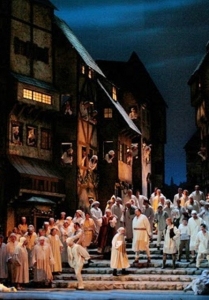

The ensuing 90 minutes is mostly an intense battle of emotions, talk that goes on and on becoming more real and direct about how the two have felt about one another from the time they chose one another (and why they say they did) until their lives together now. Then the last 10 minutes or so shows them the following Thursday night at first holding up (repressing before others the truth about their relationship), but then going mad and wild in front of these supposedly civilized friends to show their profound anger and distress and accusations until one-by-one and then more hurriedly, a group leave. We discover who is the lover (the husband’s editor on the journal he works at).

Exposed

Then that night right afterwards he attempts rape, does not go through with it, then she turns and says she is willing to make love, and has her maid take off her corset, put her in a slip and robe and lays down before him on the bed. Then after a slow burn and finally getting on top of her (with all his clothes), he can’t manage it. She says something like we’ll talk again in the morning. an inter-title suggests it’s morning now and the room are lit with morning light. We see now him in the street walking quickly away. The inter-title says he leaves never to return.

Throughout voice-over and inter-titles are used.

I watched this film because of the volume my essay on Trollope was published in, Victorian Literature and Film Adaptation, ed Burnham and Pollock. The other essay which was strongly praised (besides mine) by Kamilla Elliot was by Gene Moore, “Making Private Scenes Public: Conrad’s ‘The Return’ and Chereau’s Gabrielle.” Moore says Conrad’s tale focuses on a uncomprehending husband who is mocked; in Conrad’s story the wife is nameless. Moore also says the film focuses on the wife, and has been ignored by Conrad critics (mostly male I’ll guess). In a 35 minute feature made up of interviews with Chereau, Huppert and Greggory, Chereau says his film is about the husband’s falling to pieces, shattered carapace and then what we see; his vulnerability. He is no fool in the film; he surmised she was gone (we feel) upon seeing the note; sex (we learn from their dialogue) has not been good for years, never been good. Chereau insists this is a timeless situation — within the context of nuclear middle class families so say European arrangements since medieval Europe and until today, I’d agree and I’d agree he does transcend this particularity as the two people dig deeper at another and slowly go wild from within.

But the film is also clearly about the wife. She is named. She is continually under the camera’s scrutiny. The camera is him staring at her.

The writer is a woman: Anne-Louise Trividic. Chereau kept referring to Anne. The feature had Isabelle Huppert talking about her role just as much as Pascal Greggory about his and Chereau about the film. I’d say this is one of those rare films where we get a woman’s take on a man’s work, and the woman, Gabrielle, explains what Conrad was getting at: the husband in the film keeps asking the wife why why why did she return and she has a hard time explaining this point. Over and over. She does say that the lover she got (the editor) was someone that she feared she would sink into and give all he wanted and never hold back ever, nothing. I find that beautiful and true of sexual loving: when the couple really love tenderly it can make the books or film flower (Winston Graham’s Demelza and Ross Poldark are this way); when one of the pair is cruel, this kind of loving is profoundly destructive for the other (what would happen to Richardson’s Clarissa if she married Lovelace). But Gabrielle fears it, she fears what the man would do with it — in the salon conversation she says in the prologue you don’t need to know anything about other people to enjoy their company, in fact it’s best to keep a distance. The lover is a man who complained about vulgar art but is clearly very vulgar himself, animalistic somehow: we see he loves to eat, drink, smoke cigars, is intensely sensual as the trussed-up husband is not.

But she also says they need to face what they are, what they have been. That’s the real answer: she returned in order to face with him what they have become. She left the note in order to stage the scene. She wanted to break out. She did not want this lover but to change her life with the husband.

Gene Moore says that the film makes private scenes public and is about the violation of social rules – in particular the house has a bunch of female servants who march in and out during all this trauma, serve dinners, cook, undress and dress the wife. Moore’s thesis is very odd. He really seems to think this film is about the psychological abuse of the servants. This is skewed. It is true we are in a house of servants, and watch them hearing the master and mistress fight. We see them in the kitchen as the quarrel is going on. We see them serve the pair dinner, put the food on their plates. We see the maids help Gabrielle take off her clothes and put on her slip and robe. At one point she talks to one of them who is identifying with her and this maid for a moment seems to try to interpose herself between the master and mistress.

But surely this is missing what is the point about this more marginalized material. First there are no male servants about. No valet. No butler. The servant world of this film doesn’t make sense. Why should they be all women and perpetually cooking? Why does it take three women to undress Gabrielle? Tividic is showing us a woman’s world and this male flailing himself in it.

Further, the women servants do not seem embarrassed. There was a limit to how far the couple did reveal themselves, especially in front of servants. The most intimate talk and sudden frantic gestures and actions occur when the servants are gone. Jean stayed mostly dressed and when Gabrielle offered herself up to him she still had on her lovely silk slip and was laying in the rich red robe, as a sort of blanket wrapped about her

In his most distresed moments he remains well-bred, the courteous gentleman who tries not to insult other people, not to interfere with them:

A rare shot in the light

The husband and wife are not abusing their servants. This is not a film about servant abuse, though it is private life made public for us. Jean and Gabrielle have abused themselves, alienated themselves from themselves and one another for such a long time, that they are almost not alive for real.

She leaves and then returns to break this spell. But he cannot face what she is come home to face and he flees. It’s too threatening to his delicate poise, too emasculating. He cannot face his vulnerability to her.

This is a rare subtle film about a power struggle in a marriage where both are intensely oppressed by the routine of life demanded of them. That’s why we open with him coming home from work in that crowd. Why the action is sandwiched between the stifling performative social life. He is trying to understand this within the context of speechless rage and despair, the wounded cuckold. She is mute with a sort of helpless longing, but not for the vulgar editor.

I was so stunned by the dialogue. I wished I had the screenplay so as to read it carefully — as one does a novel. Chereau and Moore say the words of the screenplay are far different from the story. Conrad’s story is short and mostly narration. This film is long and the dialogue twists and turns and keeps up.

When I snapped the shots you see here, I discovered most came out very dark; that the film was shot in shadows. It does begin in black-and-white; when the first revelation occurs (she returns), it moves into color. It goes back and forth between black-and-white and color. It ends in black-and-white as he flees. This gives us a feel of the past frozen before us. I was thrilled by many shots showing Huppert’s beauty, and how carefully Chereau caught the husband’s cracking up with taste. The shots are like pictures, framed, very stylized, artificial. Chereau talked about his cinematographer, Eric Gautier; like Francesco Mereilles, Chereau has had one person he relies on consistently and he knows how central this man is to his films.

I’d love to read an insightful study of this film. Jim tells me Chereau is famous for a Wagner ring he did in the 1970s where he took Shaw’s analysis of the opera as about capitalism seriously. Chereau (like Francesca Zambello’s direction of Das Rheingold) dressed the actor-singers in 1920s evening clothes. That works very well.

Huppert’s career has been just a brilliant one. Chereau says he chose her for the role after he watched her in the film adaptation of Jelinek’s The Piano Teacher. I am just so drawn to her performances and the types she plays in all her films. I have written about The Piano Teacher and Claire Denis’s White Material

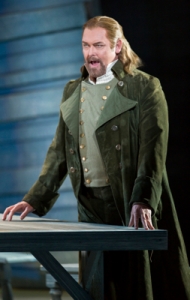

I don’t remember seeing Pascal Greggory before. He seems to me to be able to break away from the usual demand most other actors are unable to rid themselves of: that they keep up a hard invulnerability masculinity which only cracks occasionally so that their understand of vulnerability is never explored. An actor I’ve seen recently who can break this taboo at length is Martin Freeman as Watson in the new Sherlock.

I will go on to explore a another of the films that the finer film studies in Victorian Literature and Film thoroughly examined. I know that Louise McDonald’s take on Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon is spot on, but I would like to try Atom Egoyan’s 1997 film The Sweet Hereafter.

Ellen