Cliff top — Aliano, Italy, in Lucania region

Dear friends and readers,

There is no doubt in my mind that the favorite text — the one most liked, respected over this past year that I’ve taught has been Carlo Levi’s Christ Stopped at Eboli (published 1945). It’s common to call this wonderful meditative account of Levi’s time of forced exile at Grassano and then Gagliano a poetic masterpiece; it also provides a profound and empathetic explanation of how millions of people can become fascists, once again (alas) an important topic in our world today.

I offered this more concise and simple description of it the last time I wrote of it here:

It’s an ethnographic and anthropological study. It covers the year he spent in internal exile — a peculiarly Italian form of imprisonment descending from the Roman period, where a person is cut off, exiled from his or her community, isolated in a remote spot and watched to keep him or her from any kind of political activity, news of the world he or she understands. (A number of the Jewish and socialist/communist literati in Italy were treated this way: Ginzburg’s memoir includes a couple of years in Abruzzi.) Carlo Levi may be said to have thoroughly internalized his exterior culture — he acts as physician (he was trained to be a doctor), paints (his vocation), writes, joins in tangentially — which culture during his sojourn expands to sympathize with these strange and victimized (for centuries) people he finds himself among, whom since the Northerners know little of them, he is determined to bring before the world of his readers (the book was written in 1946 after Mussolini fell from power).

His conclusion that these people live in a timeless realm they cannot be plucked from is shown to be inadequate by his own account: He repeats many times that things there do not have to be the way they are; a wide government program well funded, providing irrigation, changing the financial laws, redistributing land, education, would transform the habitus and its people who have been given no opportunity, no good choices (like the working class whites of the US), exploited by every group that has taken power over them, and the result has been seething just repressed destructive violence. (The lesson for our era is more direct in Carlo Levi’s book’s conclusions than the above books.) He compels our attention by the riveted and insightful nature of the chronological settling in and living alongside story he tells. His sister visits him at one point, and we see this world from her experienced sophisticated compassionate eyes she registers shock and horror at a majority of children suffering from malaria, insects, uneducated, dressed in rags, with no hope for a better future than unending hard farm work which barely supports them — and is not enough to pay the overlords demanded taxes.

A detail from one of his embracingly beautiful depiction of the people of Lucania

***************************************************

So let me go a little more into detail as it’s so relevant to our world today

The title of Levi’s book is a proverbial phrase often repeated by the local peasants and which `in their mouths may be no more than the expression of a hopeless feeling of inferiority. We are not Christians, we’re not human beings’. Levi explains its much deeper meaning: Eboli is `where the road and the railway leave the coast of Salerno and turn into the desolate reaches of Lucania. Christ never came this far, nor did time, nor the individual soul, nor hope, nor the relation of cause and effect, nor reason nor history’. Levi says in the second half, to begin reform you must begin to eradicate this idea they are inferior and their lives worth nothing. An intense empathy at the same time as he does not sentimentalize these people – he sees them out of clear sceptical disillusioned eyes – Levi mediates a gap between them and us. A new world cannot come from the plans or documents of a few enlightened men (and/or women).

The book sort of divides into two parts. Until about Chapters 12-13, we see him enter this hovel, what life with the widow is like, and get a series of portraits of fascist officials, then specific types (rather like Chaucer) of people doing specific jobs (postmaster, inspector, tax collector), all humanized, given psychological and social depth. The first half of the book might be described as his search for a place he can live with some hope of enacting his professions as a painter and now doctor. It takes two attempts: first he goes to live in a crumbling hospital-prison; then one of the upper class people in the village has a vacant three room building which can be turned into kitchen, bedroom, and studio, with a balcony. Levi then acquires a housekeeper and cook Giulia Venere, and settles in. But each step enables him to develop ideas about the place and people. We see the murderous (because so desperate) internecine family and frenemy politics, men who went to the America (mostly NYC) and having made a little money (almost inexplicably) come back to live in poverty once again – who they are and how they now live. Through the women whose children he cares for and a failed attempt to hire housekeeper and then successful one, he tells of the average lives of these women, almost perpetually pregnant, and most of the pregnancies not from husbands – gone away for years, many of their children dying, they too in their houses long hours of primitive tasks, the most important of which is food production.

The second half after he sets this up we get longer sections on history and politics, and some festivals he experiences, his own trip to the previous place he lived, home, his failed attempt to do something about the malaria. Levi here expatiates in compelling tales his political and philosophical point of view: we learn of the later 19th century wars of brigandage in southern rural Italy – a precursor in fascism. Though they had no political or philosophical POV Levi does adumbrate his political and philosophical point of view in his review of the wars of brigandage – a precursor in some ways to fascism, though they had no political or philosophical POV.

I find the whole long section about bringandate extraordinary. I know few texts like it. Among the utterances in this section are the crazed ideas that he quotes people spouting; they remind me of the crazed ideas Trump manages to evoke from his “base” as it’s called. People saying things you just don’t know where to begin to try to convince them otherwise

Basically he argues to have a real revolution one must break with the past. Italy never developed a full middle class bourgeoisie across the country; those who were middle class had developed through compromises with the upper classes – protectionism, rifling of state and taxpayers coffers; they absolutely excluded from any power working and lower middle class people. He was against notions of resistance; fundamental problems are too deep. This apparent passivity and unchangingness (which is what we find asserted in many reactionary and conservative books) is born of hopelessness and an inculcated sense of inferiority; what you have beneath that is a ferocity born of despair. His description of these people could describe Trump’s armed people on Jan 6th.

He also argues elsewhere (a book called Fear of Freedom) people are afraid of freedom; they fear liberty -this is very like Rousseau. Man is born free but everywhere in chains. To which a 19th century philosopher said this is to say sheep are born carnivorous and everywhere eat grass. A critique of western civilization – not to speak of tribal life. Religions seek certainty and stability in rituals and myths. Each life is an individual journey. Inherited codes and practices are only a kind of outer skin or protective layer – law, which must be reinterpreted over and over as circumstances and needs change.

The Risorgimento was basically the take over of all Italy by the form of government that had evolved in the north, in Turin and Piedmont and it wouldn’t do. It emerges from the Napoleonic take-over (invasion) of Italy which provoked the individual states and regions to go to war against the colonialist powers who had taken over Italy before Napoleon: Austria and France in the North, Venice itself over others, Spain in the south, the Ottoman empire, the south west: gradually after a series of wars, defeats and successes, until a culmination in the battles fought by Garibaldi, backed by the philosophy of Mazzini, and ideas of reform from Cavour, this Rising Again, took shape. One obstacle I’ve not yet mentioned was the Catholic Church and its grip on Rome; that was not broken until late in the 19th century.

What he does in his one fiction and his memoirs and travel books is reveal the inner workings of a society as a sort of anthropological study with the aim ultimately of emancipating people – of course now you come for gov’t helps in health, infrastructure, education. But that’s not the heart of what needs to be transformed. He much admired Antonio Gramsci another complicated brilliant man who was not directly murdered in prisons but whose health and selfhood so destroyed (like Oscar Wilde) 3 years later he died at home. But more important is a politics of position. That is achieved by getting purchase on what people remember, what they think is their history, what they read … That is by education. It’s crucial to educate people to know and think (if you are determined to control them) what favors you – that is what all this banning of books and unashamed attempt to repress modern education in schools and colleges is about. Books which reveal the true history of enslavement in this country, the Jim Crow era (a regime of terrorism) are crucial to teach so as to enable people to know who they are – and also in forming identities. People are sheep. Films and books matter.

The old order is dead. The new order cannot yet be born. In this interregnum a variety of pathological symptoms arise — Gramsci — that is what Levi is showing us in southern Italy

Levi’s book combines a people outside of History with Hope. He shows them being crashed into by History – in the form of the State – demanding taxes, conscription, its officers controlling people – but he sees hope of change

Families have been dispersed, houses devastated, property destroyed, states overturned. If these ruins were only material the world would quickly go back to what it was. But the old sense of the family has been lost, the old sense of home has changed, the old sense of property no longer has the validity it once had, the old sense of the State has lost all power. And something deeper has changed in men’s souls, something which is difficult to define, but which is expressed unconsciously in every act, every word, every gesture: the very vision of the world, the sense of the relationship of people with each other, with things and with destiny [from another text by Levi written in 1944].

He is convinced history is of essential importance even if the average person cannot see this, pp 137-38 Shakespeare’s earliest plays are histories – Wars of the Roses, government’s being overturned, tyrants emerging – he does not defend brigandage – of course not9 – but we need to understand it. One problem with the Jan 6th hearings is the kinds of questions people are allowed to ask in modern courts of law do not elicit from the answerers what we would like truly to know about them. Levi can find food for thought in the classics because he reads them – as it were aright. On p 141 we see him considering Virgil’s Aeneid not as it’s usually discussed but to bring out what Virgil is silent about.. Very violent societies – state (Trollope says) is that level of organization which has the monopoly on violence in any given area – that’s neutral but you can have different ways of electing and choosing that state. Blind urges to destruction gets us nowhere (that is what we are seeing the present GOP under Trump attempting today).

In a museum in Matera — a woman and children

There is much to entertain too. Funny stories: two men forbidden to carry on their relationship as resisters leave bowls of spaghetti out in a specific place for one another so they can eat the same meal at the same time. A story of resilience. There are poignant retellings of womens’ lives vis-à-vis their children. When he makes a serious attempt to get the local authorities to do something about the malaria, his license to practice is taken away. He submits a plan that worked in Grassano, and the Gagliano mayor forbids him to practice. This prohibition does enrage and rouse the people. At least one man dies directly as a result of his not being able to help him; another man has a ruptured appendix and every effort is made by his brother and Levi to get Levi to his side. They do not have the arms or wherewithal to riot as a mob, so they put on a play where they enact the roles of the people who truly are oppressing them as comic and horrible monsters. (There is also a Christmas play). He feels for animals and makes us feel for them: the women are forced to neuter their pigs and the ritual terrifies the women and the pigs: Levi describes their ordeal graphically.

There is cheerfulness too. For unexplained reasons Levi is given “time off” or “away” from Gagliano, to return to the more middle class Grassano, a sort of vacation from the monotony. He goes to cafes, participates in games, talk; among other things, the towns people also put on a play. He is treated like some kind of star. I felt he was treated as an extraordinary person and this worked on his sensibility a bit too strongly. But at the core of this book is his love for these people (although he cannot live here, does not belong) and atttempts to help them. The last couple of pages of the book repeat his political and moral ideas and are a vow to enact them politically if he survives. And he did.

***********************************************

I conclude with a little life:

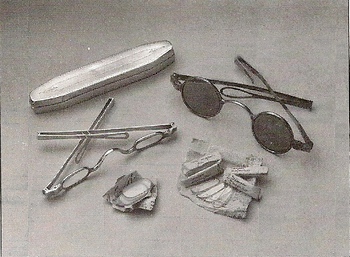

His years were 1902 – 1975. He grew up in Turin, both parents wealthy, his father a doctor. Levi trained as a doctor at first – we see that ability come into prominence in his time in Lucania. His sister with whom he was close and whose visit to Gagliano (as I said), provides an important section of the book – she brings some tools of his medical trade, some tools for his painting trade; a stethoscope is unheard of in this place. Luisa’s astonishment and shock when she visits this rural southern part of Italy for the first time enables us to see the place through the eyes of someone never come near such a place – horror especially at the children covered with insects so diseased so young – none of it necessary (she says and knows as this does not exist in the north). The theme of the book, through her eyes is, someone or people elsewhere have made the choices which lead to this environment and the peasants knowing no hope or nothing better have acquiesced – but are in their deepest selves very angry – whence among others fascism – we are seeing something of the same thing here in the US. Sister is a child psychologist, pediatrician at a time few women in Italy were highly educated and she begins immediately to make plans for people to enact on these people’s behalf.

By 1923 Levi had been living in Paris as a painter; by 1928 he had given up the profession of medicine and become a painter – and went back to Turin. He was also in Rome where he lived a good deal in the later part of his life. 1934 the year he was arrested for anti-fascist activity was the same year Mario Levi swims to safety in Switzerland; Levi had founded a party calling itself Justice and Liberty – 1929. Ginzburg belonged – so that’s how Natalia met him. There were spies or moles everywhere and one who presented himself as a pornographer (he had to pretend to some talent) was a member of the secret police. In 1936 Levi was released and moved quickly to Paris until the fall of Mussolini. He joined the Political Action Party (see just below), influenced by a politically active man named Gobetti (also turns up in Family Lexicon) edited papers and returning to hiding wrote. He took refuse in Southern France and also the Pitti Palace in Florence where he is said to have written Christ Stopped at Eboli. Throughout the 1930s, 40s fascist police a constant threat. Christ Stopped at Eboli was published by Einaudi for whom Natalia worked – so too Pavese and others – a very in group.

One of Levi’s own paintings: a vista, a view of Aliano

After the war, he met the woman who became his partner, Lenuccia Salva. 1950 he edited Italia Libera, identified as the voice of Partito d’Azione (Action Party). He wrote one novel, The Watch (Orologio) using some of this journalism I Rome. He was imitating non-fiction works – in the experimental mode popular among the more artistic – -elite – since Joyce’s Ulysses, Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway. They play games with time. The watch occurs over three days during which time the protagonist has lost his watch. He is doing for Italy and Rome after the war what he had done for Lucania during: recording life culture politics impingement of history. He wrote another marvelous meditative book about Italy just after the war: Fleeting Rome.

He lived a life of energy and fervor – he painted away, had lots of exhibits. His experiences in Sicily ae another semi-autobiographical book, Words are Stones (Le parole sono pietre) won a prestigious prize. Traveled to Germany & Italy and recorded what he saw – one book called The Future has an Ancient Heart. I like that. 1963 elected Senator on the communist ticket, died of pneumonia in January 1975.

Levi left much of his writing out of print or scattered and in 2002 was published Fleeting Rome, wonderful book – in seach of La Dolce Vita. Posthumous. There is no biography in English, and no inexpensive one in Italian or any other language. He was a communist; communists are erased; in the 1930s they didn’t get prizes, stories about them didn’t get prizes …

Christ Stopped at Eboli had a hard time penetrating the US market; early reviews by US people condemned it (this was the 1950s remember – with McCarthyism and John Birch Society on the war path) as propaganda. It made its way slowly and a film made hardly seen in the US Francesco Rosi, Christ Stopped at Eboli, a sort of neo-realistic documentary (1979) I have the first half of a faulty DVD set; the second disk is missing. There are Wonderful features about the making of the film, the director and Levi himself.

Filmed on location, here is the stairway leading up to the house Levi lived in.

He was buried in Aliano and today people come to tour Aliano to see his house; various signs tell you what he did here and there.

I must not leave out his dog, Barone. The film shows him taking Barone on by chance; in fact, he told people he wanted a dog for a companion, and this dog was a beautiful good-natured stray (in effect) and he was given him. Barone today is buried next to Levi’s father (presumably in Turin). The photo at the beginning of this section is of Levi and Barone.

Ellen