Dear friends and readers,

A major 19th century woman novelist, travel writer, Woolson depicts the south after the civil war, writes visionary landscape of the great lakes (ice and snow), realistic novels, with (in effect) feminist stance, very enjoyable travel writing. Anne Boyd Rioux has written a fine biography showing what the career of a women of letters in America was like — obstacles many. Woolson moved to Europe. And of course the deep friendship with Henry James. She situates herself among the major women novelists of her generation, knew quite a number of them, translated George Sand, never forgot Jane Eyre. She even liked Anthony Trollope, his autobiography, admired his relentless traveling:

“Anthony Trollope’s Autobiography, yes, I have read it. It gave me such a feeling! Naturally I noticed more especially his way of working. What could he have been made of! What would I not give for the hundredth part of his robust vitality. I never can do anything by lamplight, nothing when I am tired, nothing–it almost seems sometimes–at any time! . . . And here was this great English Trollope hauled out of bed long before daylight every morning for years, writing by lamplight three hours before he began the “regular” work (post office and hunting!) of the day. Well, he was English and therefore had no nerves, fortunate man ….

I have no less than five or six books to recommend (!), or to make this sound less like a task of too many pages, an author you might not have heard of, or only heard of as a rejected mistress of Henry James, now known to have been if not actively homosexual (he probably quietly was), at least as regards heterosexuality celibate: Constance Fenimore Woolson wrote splendid novels, novellas, short stories and travel books in the post-reconstruction era of the US, from her escape sites in Europe, mostly Italy. Over the past couple of months, I’ve read her powerful first novel, Anne (which ought to have a title that gives some sense of its content, e.g, An Internal Exile) in an edition, which included the original touching and expressive illustrations:

The heroine’s aunt, Miss Lois,

A striking minor male character ….

a few remarkable short stories and gothic landscape fantasies, in Castle Nowhere, and her depictions of the bitterness of the defeated southerners, immersed in death, near bankruptcy (those who had been wealthy had been so off the bodies and minds of their slaves), and destructive self-thwarting norms, best read as a group in Rayburn S. Moore’s old-fashioned “masterworks of literature series, For the Major and other Stories, though a couple are reprinted in Rioux’s Miss Grief and Other Stories. Anne Boyd Rioux’s Portrait of a Novelist (the title modeled on Gorra’s) also depicts the norms and prejudices that marginalized and erased American women fiction writers of the 19th century (see her Bluestocking Bulletin). Woolson is a major American voice of the second half of the 19th century. Try her.

Unfortunately, Woolson is best known for either having accidentally died or killed herself at age 54 by falling out a window in Venice, probably (it’s thought) because she was rejected as a romantic partner by Henry James (see Ruth Bernard Yeazell, “In what sense did she love him?”, LRB, 36:9, 8 May 2014). Often this event which Rioux presents carefully is treated as a ridiculous joke because Henry James, so upset at what happened, came to help with her effects, and distressed attempted to drown Woolson’s dresses in the Venice lagoon and they all floated up around him. What happened is a combination of life-long depression, and some serious illness in her early fifties (not uncommon before there was an understanding of various human organs) led to a decline, too much medicine, bad pain, and a half-willed suicide. Woolson is a major character in Michael Gorra’s Portrait of a Novel, a psycho-biography of Henry James’s creation of the story of Isabel Archer, and not overlooked altogether by Colm Toibin in The Master. That she has at long last arrived may be seen in a volume of critical essays devoted to her:

.

.

It’s said though that the shared or mutual hidden or inner lives of James and Woolson is portrayed best by Lyndall Gordon in her biography of Henry James.

********************************

I’m going to differ from most accounts by my emphasis and what I recommend to start with: the travel books, say The Benedicts Abroad (a family effort) or better yet, her own Mentone, Cairo, and Corfu, which, like Anne, comes accompanied by lovely appropriate illustrations:

It’s a perfect summer book; perhaps you can’t afford to go to the Riveria this year; it’s the closest thing as a read I’ve come across to the once wonderfully evocative Miramax movies of lonely sensitive reading people traveling to some dream place, e.g., A Month by the Lake (Venessa Redgrave and Edward Fox in an H.E. Bates’s short story). A group of variously witty, desperate, amused, and knowledgable (about the undersides of history, geology, biography, tourist sites) have awakening adventures together.

Then instead of plunging into a longer novel, read some of her short stories. In the US the fiction writer did not have to produce three-volume tomes for Mudie’s Library, or the Cornhill or other similar venues. You won’t forget “Rodman the Keeper” or For the Major. Rodman is one of Woolson’s many solitary souls, a caretaker for a national cemetery of the union (pro-Northern) dead; like most of the central characters of Woolson’s stories I’ve read, he tries to retreat from society insofar as he can, but is dragged back in by his conscience and need. He comes across an impoverished dying ex-confederate soldier who is not at all reconciled to defeat and nurses this man through his last illness. This is centrally about the devastation of the civil war and the complex hatreds in the aftermath, the beauty of black people’s magnanimity, generosity of feeling, living down south still. Again the illustrations are remarkable:

For the Major is about intensely repressed lives where the gradually emerging white heroine has misrepresented everything about herself for years. There is insight, some degree of self-acceptance and fulfillment by breaking through taboos but no false redemption. Woolson provides the source of the hatred of the south for the north well into the 20th century and even the 21st. I hadn’t thought about how the conquered might feel in a situation: a woman’s apparently non-political fiction gives us the inner life of the impotent rage then turned against black people who since they represented a large percentage of the population would have had to be given real freedom for the region to thrive; the southern characters refuse to stop pretending they are rich aristocrats. They will not admit to having disabled people in their families. They will not permit women to live independent lives apart from marriage (now more or less out of the question as so many had died. There are flaws: while she does depicts black people with real empathy and dignity, she also portrays them as helplessly loyal to their ex-owners as if they cannot make their own lives.

,

,

The title story of Castle Nowhere reads like a distillation of the opening sequence of Anne. It’s set in a region of Michigan, the islands of the Great Lakes of Michigan, Woolson spent formative years in: like the opening of Anne, it reminded me of Daphnis and Chloe, or Paul et Virginie: an intensely solitary group of people live a quietly ecstatic existence in a dangerously cold, ice, snow and lake place. They succour one another and are deeply fulfilled. Tyler Tichelaar suggests this particular story focuses on a aging male solitary wanderer, but there is also a fairy tale element as the loving heterosexual couple who emerge (as in Anne) end up with a deeply contented life together. It can also recall the 1790s Radcliffe-like gothics, only the “machinery” or furniture is that of the wild landscape and hardships of mid-America. The bleak yet exalted (in Woolson’s curiously postive way of writing gothic) landscape of a spiritual lighthouse existence in St Clair Flats contains the same beauty as Woolf’s novel of creativity and aspiration.

I don’t know if “Miss Grief,” possibly the best-known story by Woolson was first published among her Italian stories; it has been interpreted (like Jupiter Lights, a late novel) as feminist. It is the one story I’ve read that directly concerns her life as a novelist. Like For the Major the narrative voice is that of implied sardonic irony: a fatuous complacent money-making successful male author finds himself besieged by a Miss Crief whose name he hears as Miss Grief. No one will publish her work, but when under intense pressure he begins to read one of her stories, he finds it has passion, strength, sincerity his lacks. Woolson wants us to feel precisely where and when this man is shallow his work is popular. Miss Grief reads aloud precisely the passage from the author’s work that he knows he is most authentic in, and he is riveted by her and her writing. But she will not temper it, will not eliminate half-crazed elements, will not change the plot to be acceptable story so the work can’t be sold. She has a great play but in order to get it performed, she must compromise. (This sounds like her sympathetic account of James’s own theatrical failures.) The story ends melodramatically with her happy death. She has had the fulfillment of his approbation. Some have read the story as about James and Woolson, though it was Edith Wharton who made the huge success, and during her life Woolson made a great deal of money on Anne and was well-known, respected and reviewed (if not favorably by Howells, who, like Hawthorne, seems to have wanted to marginalize women).

****************************

Another illustration for Anne

Of the longer works I read but two but liked them both. Anne was Woolson’s first long novel, and it’s very strong until near the end when it collapses into melodrama. People have written about her books to place them alongside Henry James; it’s more accurate to see them in the context of other women’s books, women’s writing, and visionary landscapes. The book opens on Mackinak Island in the straits of Mackinac where the upper and lower peninsulas of Michigan meet, near the top of Lake Huron. the descriptions of ice, snow, waters are visionary. The story is of a highly intelligent young woman living a semi-solitary (again) impoverished life on a frontier who is willing to sacrifice all to the needs of her desperate family; she finds herself deeply congenial with a young man, Rasta.

The motif of the boy and girl growing up together in a world of snow and lakes repeats itself

Woolson has affinities with the work of Willa Cather: Woolson is even drawn to ethnic French people. As the novel progresses, Anne is forced to leave the island – for money, for schooling, to grow up — and she gains female mentors along the way. In this and the love affair that Anne flees from to avoid transgressive sex recall Jane Eyre. The first is the loving spinster who lives on the island near her family, Miss Lois, quietly in love with Anne’s half-philandering self-indulgent father; she is taken in by a hard mean aunt but finds friendship with an older generous and sophisticated friend, Helen Lorrington; when later in the book she becomes desperate for employment she is hired and kept going by a French teacher, Jean-Armande. Anne is betrayed by her French half-sister, by the educational system which develops the more shallow aspects of Rasta’s character, and finds the upper class mercenary social life of her rich aunt appalling, unlivable in. This anticipates Ellen Glasgow. In fact except that there are powerful depictions of the civil war (which the book’s time frame crosses), Woolson’s book could fit into he (dismissive) chapter on women writers in Alfred Kazin’s book On Native Grounds. She is not interested in socialism, not a political muck-raker; instead she writes l’ecriture-femme about women’s lives. Anne’s continual flights are from the situations women are put in to push them into narrow schooling, marriage, and motherhood. The men in the book are wastrels, weak, and (alas) all of them at some point in love with Anne, but here the psychology of courtship, the rivalries, are astutely depicted. I believed in the characters.

A depiction of Anne towards the end of the novel

Another worthwhile novel is East Angels. It’s about how woman as a woman spends her life hiding her inner self, and has been likened to Turgenev’s novels. She threw a great deal of ambition and adult emotion from within her artist’s life into the book. Rioux suggests the only way this heroine can “maintain her self worth” is to “maintain her self control.” Male critics, espeically Howells panned it (they didn’t believe in this heroine), but a number of reviewers an readers too felt it showed “her remarkable powers of observation,” great art (see Rioux, pp 174-178, 200-202). East Angels sold much better than James’s work at the time, if not as well as Anne, and is in print as an ebook

Rioux’s excellent biography is very good from the angle of revealing what life was like for a woman who might aspire to be a serious writer in the US in the 19th century. I have read a few lives of and some fiction by 19th century American women writers, but and until this book my knowledge of what American women specifically were up against was minimal. Rioux cites Kate Field, the woman Trollope loved who lived as a modern woman writer, traveling, lecturing; the life and work of Louisa May Alcott and Harriet Beecher Stowe are part of Rioux’s earlier context — as well as finishing schools for upper class girls. The depiction of the way sacrifice was inculcated, the way motherhood and wife-hood was used to leave no room whatsoever for individual development, what was one of the best schools, which Woolson went to, but how it had no goal for the woman to use her knowledge — all bring home to me that it was much more difficult in the US than the UK to become a woman of letters. No wonder Woolson fled to Europe. While she loved the elite and old Spanish cities of the south and Florida, and dutiful as she was to her mother, and finding deep companionship with her father, Woolson could not get herself to publish a large major adult novel until she went to Europe.

Rioux’s depiction of Woolson’s career as a journalist is again a story of a woman up against exclusionary practices and a demand she not have a mind of her own. In her stories what was wanted was pious moralizing and she resisted that. She was pushed into imitating Alcott for her first novel, The Old Stone House, a children’s novel. She translated Sand’s La Mare au Diable but it was not published! Alas. Someone else had translated it. I wish hers had been published too: She is also a strong reader of George Eliot, admires Elizabeth Barrett Browning. She is a little too earl for Edith Wharton. She tries poetry, but discouraged by others’ responses gives it up with the argument novels are as important.

I found a house, at Florence, on the hill

Of Bellosguardo. ‘Tis a tower that keeps

A post of double-observation o’er

The valley of Arno (holding as a hand

The outspread city) straight towards Fiesole

and Mount Morello and the setting sun, —

The Vallombrosan mountains to the right, …

No sun could die, nor yet be born,

unseen by dwellers at my villa: morn and eve

Were magnified before us in the pure

Illimitable space and pause of sky

— Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh — Woolson told friends in letters to understand how she felt about her home in Florence, read this passage( the 200 year old Villa Bichieri is photographed by Rioux in her book)

She had been responsible for her mother from the time of her father’s death, the loss a sympathetic brother-in-law also makes her sister more broke and dependent: she lived where her mother lived, with her, in elite, old (a Florida city founded in mid-16th century) moving “north” in summer (Asheville, North Carolina). But as she would ever be, she felt (and was) isolated and Rioux says of her she was a solitary author writing columns from afar. Depression was common in her family and her brother killed himself eventually because he could not cope with the demands made on him to live a commercially successful life. She had some great good luck: she had an income from investments her family set up for her; she had connections with the powerful and intelligent in the US and then Europe, especially male critics, diplomats (John Hay), and educated critics, literary friendships with men (Edmund Clarence Stedman). When her mother died, she could afford to go to Europe to cultured cities. She never came back. She found herself there — as did Henry James. Her attitude towards Europe reminded me of my own: as an American who has read so much of British literature, you feel you are nostalgically coming home.

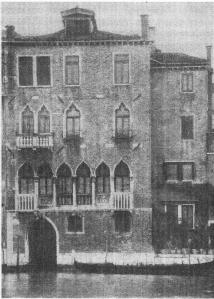

Palazzo Semitecolo, the last of Woolson’s homes, this in Venice

This is not the place to attempt to go into the twists and turns of her life nearby, with and apart from Henry James (but communicating by reading one another and letters); suffice to say Florence was central to her, and that at times they lived in the same house together, writing on different floors, in different apartments. Her deafness has been insufficiently emphasized. It began early and became much much worse. Harriet Martineau, far franker than Woolson, said the worst experiences for deaf people were dinner parties. Her work was widely reviewed. She was known to many people, including Margaret Oliphant (who did not stay in Italy, did not like travel). Woolson’s sister and her niece visited and traveled with her. She wrote sensitively of the cruelties she saw in her own nand other cultures. She lived for a time in Oxford too — and found Cheltanham dull. She chose to be alone to work, to think, because she felt unlike many people, but she experienced despair from loneliness too. She and Alice James recognized one another. She eventually became close to an American family living in Italy: Francis Boott, a highly cultured wealth gentleman, his daughter, Lizzie Duvnack, and her husband, lived near her in Bellosguardo. Lizzie’s death was one of the devastating blows late in life that led to Woolson’s own death. She kept up an extensive correspondence with Boott where she revealed more of herself openly than anywhere else (says Rioux). In her last illness, Woolson was often doubled over with pain (diverticulitis? or gripping gut as they called it in the 18th century).

The last chapter on Woolson’s after life is moving, especially her burial in the Protestant cemetery in Rome. I probably have walked by her grave. Jim and I spent over an hour or so in that cemetery one afternoon in August 1994. It is a haven, a beautiful quiet place, if your corpse is going to be buried and you remembered that way, it’s not a bad place to have your grave stone. If I ever get to go there again (unlikely) I will be sure and stand by her gravestone too.

A drawing of Woolson by Lizzie Duveneck

From James’s Partial Portraits: Constance Fenimore Woolson as reprinted in the Library of America:

I find his review impossible to characterize because on the one hand James describes Woolson’s fiction so accurately, with depth, and appreciation and on the other is continually ironic and deprecating, somehow at a distance. Were I her I’d have been very hurt.

There are also patches of the kind of prose he wrote late in life which are hard to decipher.

So first this is not the review of a friend. I didn’t expect him to heap her with false praise but this is so hedged with unspoken and implied objections. One area he begins with and returns to is the writer is a woman. That’s where he begins, when he names themes; he recurs to this over and over. She has only love as a theme. Not true and doesn’t he emphasize love in his novels too. He implies women and people complain women aren’t in positions of power, in professions, but the world of writing is now filled with women. Woolson doesn’t quite belong with these because unlike the other women writers she is not writing on behalf of getting power for women; he says twice she looks to private life for satisfaction. This shows her to be conservative. So she is put in a subcategory of women writers. At one point he says she has contradictory patterns and her short stories go nowhere — just as in Mrs Gaskell’s Cranford. I think he is objecting to l’ecriture-femme centrally.

His tone almost throughout is half-mocking, condescending, slyly amazed. It’s written as if the reviewer is amazed at some of Woolson’s attitudes: her strong morality, her apparent endorsement of retreat. I give it to him he really does minutely characterize the complicated attitude of mind Woolson projects. its nuances’ for example and he says she must be given strong credit for describing the reality of life down south after the civil war. He says this is invaluable but then turns to make fun of some aspect of her work. He finds her high-minded ness and idealisms absurd. When when he writes with high praise about the themes and emphases minutely caught in his general descriptive terms, there is this deprecating stance. He uses the word “defects” of _East Angels_ and then goes on to give over-the-top praise

My feeling is he thinks while her situations and individual characters are brilliantly conceived, he says the wholes – -the city, the culture, the larger picture — is utterly unreal. Here are characters who live in an isolated dream-like vague world where little is concrete. Yet when I think of his characters in his novels I know there are equally unreal characters

He has an awful way of referring to “negroes” as if black people were another species. Admittedly there is prejudice in Woolson’s account of native Americans and “negroes” too.

She’s translated into Italian:

A very thorough and complete summary of Woolson and many of her finest works. I loved all the images you found, many of which I had not seen, and thank you for mentioning my own blog. It definitely is time for Woolson to receive more recognition, and hopefully Rioux’s biography and others like ourselves posting about her will help bring that about.

Tyler Tichelaar

Ellen, I haven’t finished this long post yet, but thank you for this: I suppose I do see Woolson in light of James’s life and not her own literature, which I haven’t read. I like the idea of trying some travel writing and short stories: and hope to get back to the blog later today!

Sorry I made it overlong — it’s an overview and then I put details from the biography to re-situate Woolson as a woman writer. I recommend if you ever do try her, the Civil War reconstruction stories (“For the Major”, “Rodman the Keeper” are part of these), her travel writing (very enjoyable) and East Angels — the last a mature take on women’s psychology (the male establishment critics hated it).

Karen Legge: “Thanks for sharing this, Ellen. I recently read (and loved) Woolson’s For the Major. I have puchased the biography and also Woolson’s Miss Grief and Other Stories. I plan on reading a lot more of her work. Will share your blog with a friend who is very interested in Woolson.”

Me: Thank you. There is a Woolson listserv; I’m not sure of the URL but if you click on the links to Rioux in the blog you will get to her various sites and among them is this listserv.

Felipa also called in the story Philip and she dresses like a boy when we first meet her.

June 8, 2016

Tyler gave me and Clare a pdf of a story by Woolson not well known, and not very long. It’s about a wild waif on a wild landscape in Florida, whom our narrator, a woman alone and not pretty, and her friend, Christine, befriend and are close to until a male friend/lover of Christine shows up, Edward. The child is non-white and the description reminds me of Tita in Anne, making me think that after all Woolson was not so racist towards non-African-American ethnic minorities. It’s about this child’s attempt to gain approval and friendship with the two older white women:she has no chance in her life as the child of impoverished fisherman whom no one helps at all, probably she must marry young.

I’m not conveying the tone: it’s wild and strange as the child projects an identity “not civilized” — like Caliban in The Tempest, but somehow the story reminded me much more of Stevenson’s Olalla, which turns out to a vampire tale but before that also has these wild strange creatures ina natural landscape. I’ve wondered about Stevenson’s sexuality, he avoids women in his stories: that might be because he felt had to prudish if he brought them in and didn’t want to. Or maybe he had homoerotic feelings.

The story seems to me yes to reflect unadmitted to homoerotic, bisexual, lesbian feelings in Woolson towards this girl child. She is deserted with her dog whom she is likened (racist here, or cruel as the people admit but say she is like a dog). Olalla as I recall ends savagely with nothing much resolved either. It’s a gothic.

I have been on and off today reading an essay in the NYRB on Stael: Stael said the problem of the novelist is he or she has to satisfy a popular audience or the book doesn’t emerge. Stories help (Trollope and Gaskell wrote those more freely) but even they have to be placed. Time is money. Trollope had a helluva time placing his “Ride to Palestine” his one nearly open homosexual story.

Ellen

Elizabeth_Boott_Duveneck00.jpg

This portrait is at the Cincinnati Art Museum. I grew up in Covington, Kentucky, only a few blocks from where Frank Duveneck lived. I first saw this portrait on a field trip to the Museum when i was in sixth grade (a very long time ago indeed) and she has haunted me ever since. I believe this costume was her wedding outfit. If this link does not work, just google Elizabeth Boott Duveneck images and it and others will be there. The bronze memorial is at Cincinnati also and was so sad. I liked the portrait more.

Thank you. Rioux’s book has a large number of memorable portraits of Woolson’s friends. Some different ones of James than are usually trotted out.

Thanks so much for this great overview of Woolson. I had never heard of her until I took a class this spring at Politics and Prose on American Women Short Story Writers given by Elaine Showalter. We read “Miss Grief” and the biography of Constance Fenimore Woolson was mentioned. Because her books are so hard to get (or expensive) in print form, I ended up downloading her works on my Kindle and just finished Anne. It is so hard to believe this great book fell into obscurity. I loved it but agree that the last section was very melodramatic. Perhaps you would consider teaching it some time.

Susan Kavanagh