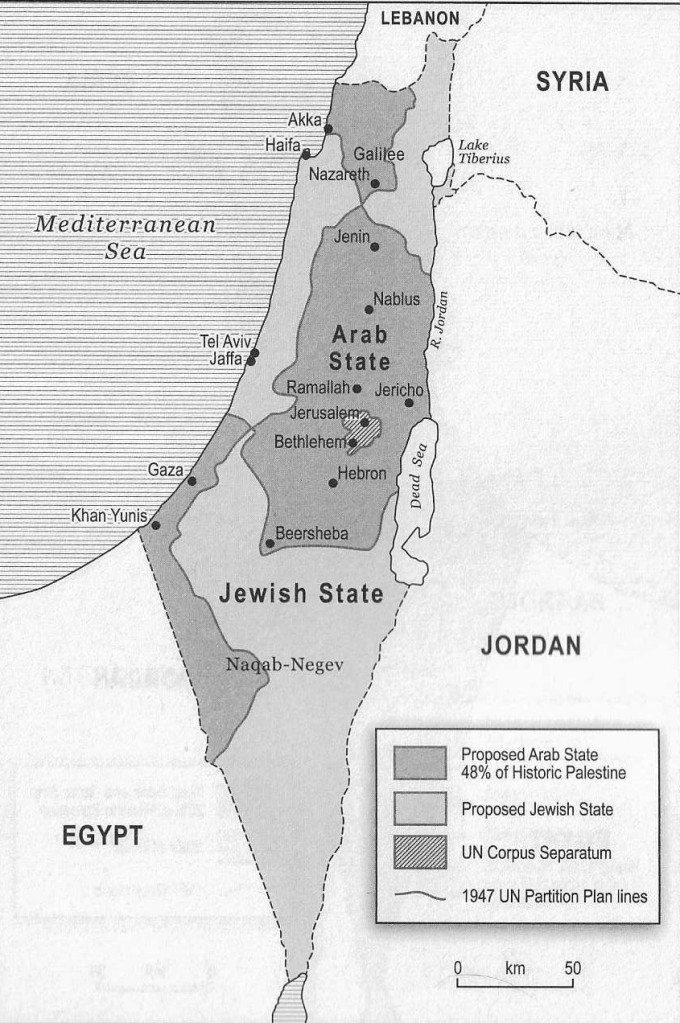

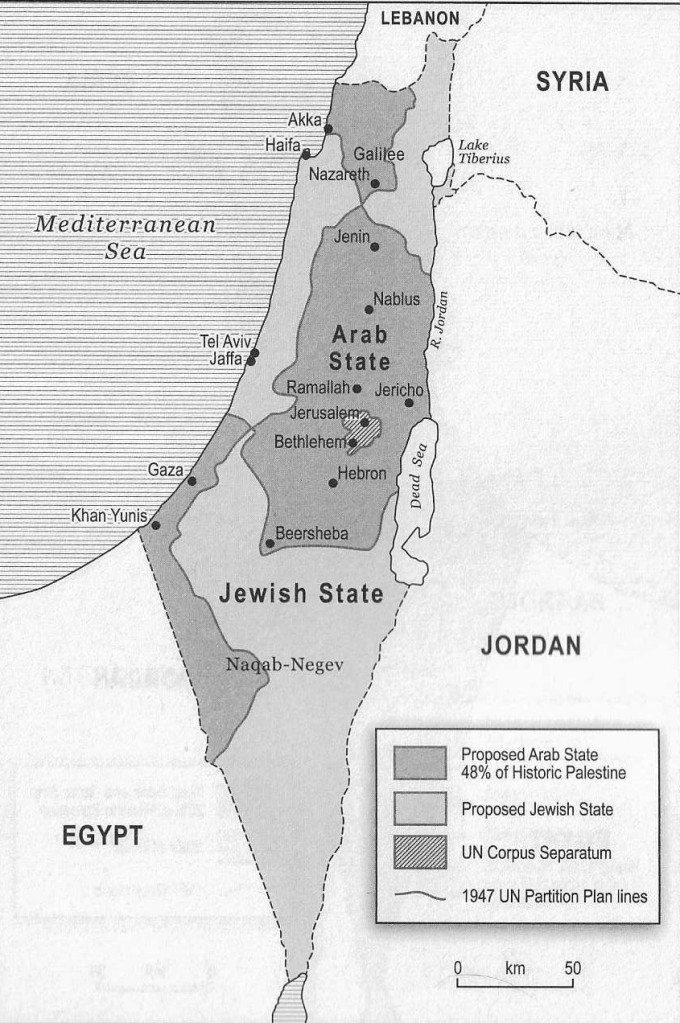

1947 Map of Palestine: from National Geographic

Friends and readers,

Being of an intellectual disposition, as I have watched with distress and horror the unfolding massacre in and continuing destruction of Gaza and step-up of illegal settlements of Israeli and displacements of Palestinians from the West Bank, I have been wanting to read a good book on what happened in 1947 and 1948. I had read years ago a historical novel, Tolstoyan type, which tried to explain how the Israeli army managed to destroy most of the Egyptian air force in June 1967, leaving its army open to successful attack.

In the Eye of the Sun by Ahdaf Soueif, is not at all pastiche, but very contemporary in language and feel. Soueif mentions Tolstoy as her master. Here she is retelling what she suggests is the crucial war of the century, and how the betrayal of Egypt (its defeat) was engineered with Britain’s help, and fostered by some of the elite of Egypt too.

The Egyptian authorities deliberately allowed Israel to strike first in that war and so gave it the opportunity to destroy the Egyptian air force. Having wiped that out, it was relatively easy for Israel to win the war. Soueif indicts the incompetence & rivalries between different Egyptian people in power but what is striking to this reader is how she is careful to include someone saying to someone else, the Israeli planes are on their way a day before June 6th; that is June 5th. I remember how nervous the other character became, fearful that if Egypt hits first, Egypt will be the aggressor, blamed, and then the US will outright attack Egypt. But the US has not been in the habit of attacking other countries along side Israel whom Israel wants to destroy in some way.

This idea that Egypt dare not defend itself from Israel’s surprise attack because of fear of US retaliation emerges as false since what happens is the surprise attack not only pulverizes Egypt but allows the rest of Egypt’s army to suffer horrendous casualties. Whole units wiped out. It is really implied this was collusion of some sort — could it be that those in authority were thought to want a capitalist order to replace Nassar’s open socialism — remember he nationalized or wanted to nationalize the Suez canal. He was replaced by Sadat a pro-US person (pro-capitalist).

This is the Israel-Palestine proposed before the 1967 war: had this remained the boundaries of these “states” what happened this past month would not have.

It would seem there was a sizeable body of violent people ready to shrink (take away, steal) the Palestinian lands much further, and they were aided by the “western” capitalist countries (US, UK) and Egypt

If you want to read a summary of this, look at Marilyn Booth on In the Eye of the Sun, in World Literature Today 68:1 (1994):204-5.

It seemed to me though, it was no use to go back partially, to these various steps whereby the colonialists took more and more land until the tiny Gaza and vulnerable West Bank were formed; what happened originally in that first crucial expulsion of 500 plus villages. Well that’s where Amy Goodman supplied the historian: Ilan Pappe who has written several books, the most important being The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. It is a very expensive book; something like $9 for a kindle but a real book well over $140. I found on sale an MP3 set that will be coming by mid-November.

But since I have to take into consideration my reader might not him or herself want to read or listen to 400+ pages, and myself couldn’t wait, tonight I can share two reviews, and an early draft of Pappe’s book and summarize all this for you. The two reviews are Seif Da Na’, a review of Ethnic Cleansing (&c), Arab Studies Quarterly, 29:3-4 (2007):173-79; Uri Ram in Middle East Studies Association Bulletin of North America (MESA), 41:2 (2007):164-69; the draft is an essay by Ilan Pappe himself, in effect a first draft for the early chapters of his book, “The 1948 Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine,” Journal of Palestine Studies, 36:1 (2006): 6-20.

What Pappe shows is it was not a war which displaced and turned 800,000 Palestinians into refugees, but a carefully worked out plan, based on minute detailed studies of the Palestine land, so that all the buildings and families and people in the villages could be rooted out by intimidation, outright violence, execution, sometimes in a blitz-like strike. A forcible expulsion; he names names, describes the whole of the operation. It is chilling. I have read of something similar in a review I did of an earlier pitiless extirpation and expulsion in Northeast Canada, of the Acadians (Christopher Hodgson).

There is much more to be learned from Pappe: I could afford (for $18 as a hard cover) his The Biggest Prison on the Earth: A History of the Occupied Territories [=illegal military continual operation]. Here he takes you through the various phases of a 75 year history of expulsion, pogrom, with the intervening wars and the attempts by the US, UK and other EU style “western” countries to get the Palestinians to accept a stasis two-state solution, which it’s hard to say if they would have accepted but Israel itself never wanted that (and thus helped build up Hamas against Arafat).

On the matter of this book (life in the “occupied territories”) I recommend (thinking of what is happening today), rather another short piece, this one published in the New Statesman, by John Pilger called “Children of the Dust (in the paper copy),” 28 May 2007, pp 26-28, online to be read. After you read let me suggest the key number to remember tonight is 40% of the people living there are children under the age of 15. Of those who survive, the rates of trauma are 99%. 6000 Palestinians are imprisoned by the Israelis. Pilger is also a post-colonial fine documentary film-maker

As Pilger says, the way most news organizations in the “west” treat the situation is utterly one-sided, in effect misrepresenting who is victim, who aggressor; but being this intellectual I went further than individuals out for their immediate self-advantage and various groups’ censorships (via media channels and control of people’s jobs), and looked to see what was the education about Palestine and Israel like. I found another excellent article (this is almost the last I will be recommending tonight!), Marcy Jane Knopf-Newman, with the somewhat unappetizing, nay unpromising title, “The Fallacy of Academic Freedom, and the Academic Boycott of Israel,” The New Centennial Review 8:2 (2008), “The Palestine Issue,” 87-110.

A good deal of Knopf-Newman’s article is dedicated to showing how “academic freedom” in universities is only for those who hold the “right” positions at a given time. What else is new? As a long-time adjunct I know it’s a cover-up for justifying tenure, which used to function as closed union shops insofar as those without tenure are concerned. What should not have surprised me and did (I didn’t know) is education in Palestinian history, going way back to the 19th century, Palestinian studies, schools, books have been rigorously suppressed: schools destroyed, attempts at colleges unfunded.

This reminds me of Black American studies in the US. But because it’s familiar does not mean it is unimportant. The Israelis and others have prevented the accumulation of a solid basis of unbiased Palestinian history to study and with which to teach generations of people and to build from. Knopf-Newman brings out parallels with South Africa when an apartheid state.

As a feminist I cannot leave out women writers: I came across a review by Samar Attar of Women under Occupation: Fadwa Tuqan and Sahar Khalifah Document Israeli Colonization” Debunking the Myths of Colonization: The Arabs and Europe. Lanham: UP of Amer, 2010. The book is a collection of brief memoirs and cycles of poems. What is the experience of women in such a place — with their children, their lack of access to jobs, education, medicine, their vulnerability to rape. One of the surprised here is this book helps account for the oddity that Christian fundamentalists in the US are so vehemently pro-Israel: they support the colonization of “the Holy Land” for their own vision of worship, the Bible. Violence and prisons are a norm of everyday life; stories of torture (and torment); the trope of a Wandering Palestinian is common.

Colonial archeologists conspire with the invasion authorities, desperately trying to find ancient Jewish monuments under the rubble only to prove to themselves that they — the migrants/warriors from Europe— are not strangers in the land, rather their Palestinian victims are. But after the shock of the invasion, the defeated narrator soon recovers her senses. Her colonizer can prevent her from crossing the border, but will never be able to destroy her imagination …

The poetry is deeply bleak, melancholy, despairing. I know about the lack of archaeological evidence from reading Digging the Dirt by Jennifer Wallace.

Which gets me to my last very short article: Donna Robinson Divine, a review of Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of Transfer in Palestinian Thought, 1882-1948. This takes us back to George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, where Zionism seems such a humane ideal, so innocent in the mystic character of Mordecai. Divine suggests that from the very beginning (well before 1917) buried in Zionist texts is the aim of transferring the Arab majority at the time inhabiting Palestine “elsewhere” and replacing them with a unmixed Jewish group of people. In order to find this out, you do have to study older documents in libraries; you need schools and centers to study.

So this is what I have to tell my readership tonight as to what they could be reading of use, essays and books of strong ethical eloquence.

Update: 12/18/2023: Final result: What does it mean to erase a people? its culture, identity, past, & aim at destroying future: From The Guardian

https://tinyurl.com/tw5pu2s8

Ellen