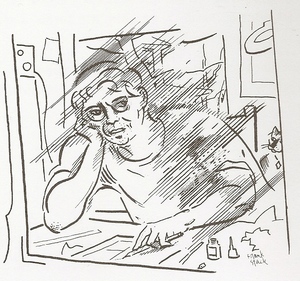

Harvey Pekar and Joyce Brabner at the time of the book

Dear friends and readers,

As those people who read my Sylvia blog know, my husband, Jim (“the Admiral”), was diagnosed with esophageal cancer this past April 28th, and he and I have been coping ever since. He had major surgery on June 3rd, and has been slowly recovering; it is probable he will have to endure chemotherapy and radiation when his natural body processes have re-asserted themselves.

During this time I have been told many success stories about people who survived nearly inoperable cancer. I have heard of a few who died. I’ve also had recommended to me books to read — to pass the time, to teach and sustain me. One stood out & I bought a copy of the graphic novel, Our Cancer Year, text by Harvey Pekar and Joyce Brabner, pictures by Frank Stack. Pekar is famous for his powerful because truthful American Splendor comics, adapted for film.

I find I often respond to graphic novels very directly and can get irritated by them in ways I wouldn’t by a sheerly written text. Have others found this? does this genre enter into people’s lives at some sore angle? I found I had a direct visceral personal response to this graphic novel about an experience of malignant cancer in the husband, Harvey, that he and his (third) wife Joyce, are sharing which Jim and I are now analogously experiencing. Harvey and Joyce live in a run-down apartment in Cleveland — the way the real Harvey and Joyce did. They have many books, about the number Jim and I probably had when we lived in an apartment.

Here they are told by the super they will have to move and argue about it

The super will later be shown to be a man trying to cheat them at every turn, trying to set up a kickback situation for himself at the same time. That this may be common shows why some people who persist in this property cherishing DIY.

I am interested in the genre of graphic novel and how it differs on the one hand from comic books and on the other from textual novels. It has depths the comic book does not have: not just the drawings which can be artful, but the text itself comes in at an angle different from that of text. There is an implied authorial and an implied illustrator presence. It is a collaborative and complex new sub-genre of the novel.

Thus far I’ve read adapted graphic novels (from Austen’s (S&S, P&P, NA), and from Radcliffe’s Udolpho; three original great ones by Posy Simmons (Tamara Drew, Gemma Bovery and Literary Life), two powerful gothics by Audrey Neiffenegger’s (Night Bookmobile and The Incestuous Sisters), and a couple of women’s memoirs (Persian whose author’s name and title I can never remember, the pictures too tiny, the writing too dense; Jewish, Bechtel’s which is really half-lies not simply autobiography with imagination; and Phoebe Potts’s Good Eggs, which I found unreadable and ludicrous). This book is closest to these memoirs by women but reaches the level of Posy Simmons’ work at moments.

***************************

Moments from early in the book (my reading & gazing experience):

Well I’m well into the book, and as yet Harvey has not gotten himself to go the doctor, undergo surgery, to find out what his lump near his prostate gland is. He knows of the lump (near his prostate) and has thought of cancer. But (we are told) he had surgery once and it was a disaster. Their lives are busy: she politically active (traveling to Israel, to Palestine); he’s a file clerk in a Cleveland hospital and writes. They make a striking contrast to Jim and my own as we were not at risk of being thrown out of our apartment, not being driven to buy a house above what we could afford, not politically activist, now armchair socialists.

Harvey and Joyce must move as the apartment house they are in will be condemned when its present owner gives it up — which he’s about to do. Harvey hates to buy a house, he is one of these US people who think the house owns them, and she agrees, but Joyce says that she will hire a handy man. (Glad to do this act it seems.) They are about to close the deal on the house, and Joyce goes to Israel because while at a conference she got herself involved with some people and takes this so seriously, she travels to this country and attempts to (in effect) interfere with their lives. She is astonished these conference friends are responding hostilely to her, differently than at said conference. Whole real contexts, experiences of their lives comes out.

She did not realize that there would be Palestinians who side with Saddam Hussein: after all the US lets Israel take over the West Bank and do what it pleases; why should Iraq not have access to the oil rich fields of Kuwaiti? The gassing of people by Saddam is brought up, but not how the US has crushed all social movements in the Middle East ruthlessly.

What gets me here is not these larger issues but that Joyce leaves Harvey in a lurch after promising she would be there for this house she wants and he doesn’t. He’s bad at email and computers. This is irresponsible given that she has reason to believe he is ill.

The airport scene where she leaves him

We cannot tell from the pictures or the text where the implied author stands in all this. I suspect we are to take Joyce’s action as right. Later when Harvey persists in carrying things to show how strong he is, part of life (is this the way we measure being part of life), while she waxes exasperated it’s clear this behavior is admired. But when he wants to throw himself out a window, all he gets is anger.

I would not respond this way to most books – it’s not just the incident but how I am made to feel somehow viscerally — yet the pictures are not great (nothing like Posy Simmons) nor the dialogue — which for once is not that self-involved I suppose. It’s a kind of stubborn stupidity, deserting the person she is attached to for people, when if she only understood reality is not her concern in this way. Have others had this experience (I wonder).

The pictures are however good enough and differ from cartoons in comic books. First they resemble the people (look above, the photo of Pekar and Brabner). Second, when the characters (for are they not characters? or is this is a diary in comic form?) when the characters are miserable, they writhe; the kind of strokes change from average comic looks to blackness, or anguished lines on white. There are many close-ups of anxious vexed faces.

The above is typical. Intimate. The drawings of places, of the offices, the hospital, of things are all resolutely naturalistic. Stack had to work closely with Brabner and Pekar: his drawings give rise to their thoughts and vice versa.

Finally Joyce drives Harvey to go to a doctor and he has a procedure. That he was anxious about this lump after all is shown by his getting up hours early — before dawn — to get to the hospital, and even after Joyce refuses to go at 3 am, getting her up way too early still and getting there at least an hour early. We see her the first instance of how she is not extra-nice or good to him, but impatient immediately.

This is not emphasized by any narrator, but is clearly meant to be there, so we have an implicit author presence. It’s not clear who is it. Often the story is told from Brabner’s point of view (that of the care-giver) and yet there is a double-author. This is another instance of the presence of the dual author different from the text in front of me.

****************************

Joyce finally hires a handywoman to fix her house continually; they bond over memories of her mother’s cancer

In the middle of the story when they finally face he had cancer what struck me is how once they are told he has lymphoma, they at first treat cancer almost as if it was just like any other of their problems. They do go BANANAs over the words and we get several frames where the word is put in GIGANTIC caps as the two characters take this information in but then they don’t proceed really to discuss the new development in any terms different than say their moving. This did astonish me. But among the stories I’ve been told I’ve recently come across one where the couple appear to be doing just that. That they are cannot be discerned.

People behave outwardly as if cancer is just another problem. They never mention the word death. I wonder if their doctors play this silence game with them. I know in hospital the usual greeting is “how are you” very brightly and the expectation is you’ll say “fine!” If you don’t, they ask why. The crass unreality of this false brightness is justified I suppose because otherwise emotionally such places would soon be messes of criss-cross uncontrolled emotions.

Well, Harvey and Joyce’s unexamined notion they must fix the house they are getting well beyond what the code violations require is what takes possession of the narrators’ minds. This leads to Joyce’s hiring their super as I said; but now he turns out to be crook and is subtracting and collecting “finders’ fees.’ That’s a kickback Joyce says. Hundreds of dollars will be spent, but she does have brains and fires him and finds a handy-woman after my own heart who confronted with a “solution” that costs $600 prefers a fix that costs $49.95. In that frame I wondered if the author saw what her characters don’t: how absurd they are in this fixing business. I can’t tell for then they go on with the renovations. Further (as in the pictures directly above), the handywoman is presented idealistically. She never talks about whether things match. The handywoman is not imbued with ideas of fashion or what “re-sell.” She is not believable.

Meanwhile the man in the story and real life too has cancer and it begins to dominate their lives will-they nill-they. They are going to chemotherapy sessions, love to talk about doctors and medicines continually (we are told). Joyce is given a schedule as a nurse like the one I had — totally indifferent to her needs. Should she quit her job, she asks. Answer: It’s up to you, with a refusal to acknowledge money or her personal fulfillment is involved here.

I note there is little open discussion between them and none with the doctors that amounts to any acknowledgement of what is at stake on any level. In our case the doctors did discuss this — maybe because we did. We did not and do not treat Jim’s cancer as if it were just another problem or vexation in our lives.

Fixing a house is a non-serious thing, cancer which brings death is not. Yet frame after frame does show the man suffering: he has to have chemotherapy and there are several frames where they are given this 12 week protocol which turns them both into continual nurses. Friends talk to them and sometimes give them mostly useless advice (go for alternative medicine) or nag at them in a scolding fashion (I would not tolerate this kind of thing for an instant), or tell stories of who died and who lived – the latter we’ve had.

On the contrary, I found neighbors gave good advice, or they tell sensible stories, or they smile and stay away

There are similar scenes of his times at chemotherapy clinics and in the waiting room.

*********************

As the book progressed towards its end, I admit I became appalled, more shocked than I usually am at stories of thousands massacred and raped.

Where the nurse cares more about disinfecting the chair than her patient and wants to eject him because his blood count is too low for his chemotherapy

As Harvey declines in strength, is subject to the pains and miseries of chemotherapy, the cold indifference and indignities of the staff: one nurse demands he be sicker or she’ll throw him out; when he does vomit from his treatment, she throws him out in disgust for that. Joyce’s unkind behavior to her husband was not just unforgivable but something I could not understand. Her mother pointed it out to here, and she justified this as “this is the way I am” and Harvey would not like anything else.

Really? He liked being scolded and threatened? He is writhing on the floor, miserable in the chemotherapy clinic, going wild with fear an pain. So she scolds him to behave better. She presents this time as her being simply irritated at being coerced into taking care of Harvey and nothing else. After she shows a film about autistic adults as part of her do-good politics, Joyce is less adamant as long as Harvey represses his misery. She says the feeling against her seems to be, “How dare she?” as if this is wrong; it’s not. She changes his pants, and seems to think he owes her big for this but she takes advantage of his debilitated state. Joyce bullies and pushes Harvey throughout.

It’s not just the big things, but the small ones. Does she help him quietly and kindly and tactfully? Is she tender in gesture? it does not seem so; the gush of sudden togetherness happens periodically but that is not daily life for a person with a fatal painful disease trying to cope with treatment that is harsh and administered with indifference.

Here I thought about the source of genuine liberal generous politics. Joyce does practice this with her vote, but what is the source of her leftism? It seems to be a practical and social bent where she wants to interfere with others, have power intimately, experience other lives intimately, and yet she does not like if the other people really tell her what they are thinking and feeling.

One sequence shows her finding Harvey near paralyzed and she curses him, hits him, damns him for two pages, she hits him with her fist and asks him what is he doing to her? He’s doing nothing to her.

The man may be dying, surely now is the time to be courteous, forbearing. And he to her. He is merely silent — while Jim was cranky at moments. She does not after this sequence behave better to him. Again there are loving scenes; of her taking his wedding ring too big for him now and putting it round her neck. But when push comes to shove, she’s not with him.

My learning curve on these nurse duties was large — I am first of all miserable at machines. But it was all mechanical. I didn’t need to learn to be tolerant, courteous, kind. I read and followed instructions, I wrote everything out I was told I had to do. In the face of high risk, my husband simply behaved the way the doctors and nurses said to, and I helped and protected him. We never lied to one another, no mincing words, and no accepting that from physicians. We demanded a minimal from one another, kept up courtesy and made jokes. We did not regard cancer as just another problem nor did we look upon ourselves or any sick person as dispensable, a cog in a crew.

Again, her political activism seemed to me a species of interfering with other people. She was not as bad as the people in the clinic sometimes were — his job is gone and he has to learn the computer while so sick. Now she ignores him and cuts him little slack. The book ends with a visit she is having from her Israeli and Palestinian friends and one of her friends helping Harvey down the stairs. (That’s not in Joyce’s instincts you see.)

We are told in a closing note that they omitted many people who did help them. This reeks of “It Takes a Village” sentimental false pretenses. We do need help beyond ourselves; there is such a thing as a community, but only a minimum is given. The closing pictures are of the two of them overlooking a park and the new house and unkempt large yard-garden they will now have to cope with. At least that’s the way they see it.

********************

One is left with many questions. How should one take the story of Joyce? Is it meant ironically? How literally true is it? Are we finally to see the story through Harvey’s point of view? His face is suddenly there in frames and many of the nicest pictures are of him. Many pictures and sequences are about his pain, his misery, his loss of his job, how he is just replaced after 20 and more years of working at the hospital as a lowly file clerk. It is insisted he learn the computer and take on a different function. Were he to have been more ambitious, risen higher would he have been treated better? This kind of specific question is not dealt with.

Their cancer year is a year of learning about many things beyond cancer but its core is the cancer. Why else name the book this way? to sell it? The book is as complicated as any textual novel but the authors are not people who question themselves or their culture deeply enough to have created a masterful novel. So they produce a book which imitates what makes people miserable but does not explain how this comes to be: it is grating and feeble (Joyce’s rage, Harvey’s refusal to buy a house all these years) where it should be exposing US values and its economic system which isolates and does not help this couple. They are a pair of victims (a very unpopular word and one not part of the vocabulary of this book). The artist, Stark, too does not have original pictorial insights — though he is capable of great expressivity with lines. Maybe he needed them (his authors) to see what was happening to them more clearly. In short it remains popular rather than important — as perhaps the movie American Splendor is.

There’s a wikipedia article on Harvey Pekar which tells of his death in 2010. It seems he died of an overdose of medicine after his cancer had recurred for the third time. (Or so the article says; we may suspect suicide.) This would be nearly 20 years later as Our Cancer Year seems to occur in 1992 or so. I’ve never read any of his comic books before nor did I see the film American Splendor.

Joyce survives him and she does look like her photo in this comic book: she remains politically active — brave woman who I find very irritating in what I’d call her neurotypical personality traits.

As for Frank Stack, he is an “underground cartoon artist” who has a very hard time surviving because he would like to practice a genuinely questioning art in the American south.

Frank Stack’s picture of himself, the last frame of the book

I do recommend the book to anyone who has experienced cancer, especially from the angle of the care-giver.

Ellen

Dear Ellen,

I read Our Cancer Year when it came out, but I agree there isn’t much plot in Pekar and Brabner. Harvey had this whole working-class autobiography thing going, where everything is quotidian, like his life. Harvey and Joyce ARE both irritating, very smart people with poor social skills, and the whole house-moving adventure-digression is very typical of the once-upscale now-downwardly-mobile suburb where they live: huge houses were for sale cheap as people moved out of the suburb. (Personally, I’d have stayed in an apartment.)

I haven’t read Harvey Pekar’s stuff in years, but my husb read some of his comics recently and enjoyed them. Harvey was an intellectual: readDreiser and other naturalists, knew everything about jazz, fought with people constantl. The movie American Splendor is great.

I’ll have to see if I can find Our Cancer Year and reread it.

Kat

Oops! I meant to say Harvey and Joyce are irritating characters, not people. Sorry!

‘The Emperor of all Maladies’ talks about this period of time in treating breast cancer; it was a kind of ‘scored earth’ approach. It was brutal and unfortunately ultimately, ineffective.

My God, that sounds like one of the most horrible books I have ever heard of. She BEATS HIM while he is dying with cancer? Is this for real? I am profoundly sickened. Why would anyone want to read about a woman who is far sicker than her dying husband, with a cancer of the soul? Am I missing something? Why would it be good for anybody who’s been through cancer or caregiving, to read about a caregiver who beats her patient? Yes, I know caregivers can feel such pain and rage, they may feel like being abusive – but if abusing and beating a dying person isn’t a gross crime I don’t know what is. Just awful.

I recommend it as a book which tells the truth about people’s experiences. Fatuous accounts which present pollyanna views make things worse as the person going through whatever they do is made to feel worse if they are presented with images they cannot possibly come up to. I meant to put across the idea that the fiction may be ironic: : it may be that we are to see that Joyce is behaving very badly when she takes out her rage and pain on the system’s victim, but I’m not sure as the authorial presence is not clearly held to.

I’m glad you have questioned this because it gives me a chance to say what is omitted from a possible important critique of American values. It does seem that my objection is only that _I_ would not behave that way since I am controlled and can see I ought not to hurt the very person who is being hurt most. I don’t say how I see this, imply only it’s a matter of my individual feeling.

I did say at the close of my blog that the problem with this book is neither author seems to have questioned their culture’s values or themselves. So for example, in this scenario the important point should have been made that the experience Joyce is having (and her great anger) is the result of larger cultural economic and social forces isolating her. Why does she get no real help whatsoever? Why are all these demands made on her? the story exposes the cruelty of the US medical system towards its patients and their caregivers. They are martyrs to a system set up to profit from them. Their choices are profoundly limited by the circumstances they find themselves in; we see how this demand “we go it alone” seeps into the most intimate of human relationships. We see the situation they are in impacting on their behavior: the nurse’s indifference is what she has been taught; the doctors shrug it’s up to you whether you lose your salary (in the US there was no unpaid leave for family matters; now there is a tiny amount); there is no communalty in this society. When she admires him for wanting to carry boxes when he can’t she is reinforcing the values values that are driving her wild.

I mentioned that Harvey lacks status and has not played a role in his job that leads people to respect him – he is not respected simply as a human being with a job that should be protected.

Roles and behaviors are imposed on them and they do not refuse them – such as the way they behave over buying a house. They have refused to buy a house for years because they conceive they must try to make it look like a magazine. They must uphold the private property values intently. Jim and I bought a house and moved in and live in it as best we can — trying for our own comfort and security,

This goes to the critique Diane R made on WWTTA the other day which I capture on my Sylvia blog: Diane wrote of the movie, Bridesmaid: “recurrent message that YOU — you alone — are responsible for YOUR OWN experience — and if you have a problem, it is due to a personal character flaw and the worst thing you can to do is to try to blame anything or anyone outside of yourself. You have to get over blaming other people. You have to stop feeling sorry for yourself. You, the individual, have to make your own experience! What happens to you has nothing, nothing to do with, say, wider economic forces. I put it this way at the top of my Sylvia blog: There is no private life which has not been determined by a wider public life (George Eliot, Felix Holt).

And that’s only one aspect of the experience. There is much to read where the two are not ironized and we can — I do — recognize ourselves.

On the issue of not looking fully, I believe that even Jane Austen does not look fully and identifies where she should critique — that’s the problem with Emma where there is a control of irony untll the end of the book when she begins to identify with Emma. MP can be read as a book which upholds coercion; and justifies the struggle and need to endure much misery and loss.

Sylvia

No, no, Sylvia. I get it completely – about showing the unvarnished truth, not Pollyanna; that it is a visceral, searing portrait of how society let Joyce struggle and suffer on her own without help; that she’s a martyr to the system; that she buckles to conformity with the silly pressures about having a house – I get all that. Why on earth would you think I would be so obtuse as not to? But you miss my point! It’s that I don’t get why or how you can seem to simply pass over – ignore – maybe even condone – a crime that is every bit as evil, bad, violent as rape. Cruelly beating a helpless dying man! No one, NO ONE is forced by society’s evils to do violence like that to another. There’s no excuse. Because somebody was screwed over by the system, it’s justifiable that they rape or murder and you won’t criticize that? You were up against a little of what Joyce experienced, yourself. In panic at vulnerable moments you had to desperately fight against a system that didn’t care, and you did just that. Did it, could it, EVER make you turn against poor Jim and punch him in the face?! You never quit fighting for, and protecting him, and never would. Why do you turn a blind eye to this woman turning into an utter unspeakable monster? How can you, who hate cruelty, just not seem to notice it? Don’t tell me how society screwing up did it. SHE hit him! Would you “excuse” rape and murder because the perpetrator had a hard life? No, I don’t think so; I think you just didn’t quite take it in.

She’s not raping and murdering him. She did hit him. She is not beating him, but she does shout at him and demand he get up. He himself bought into this (as I said) by himself trying to do things he should not. He does in the fiction the next morning get up and scream at her “how dare you?” the Admiral would not scream, but he would never forgive me I think for such a scene, or at least never forget it. Harvey does not react like that.

I have never once forced him to go to work; he has never forced me ever to go out to work. This sometimes results in people being amazed at “what you take,” such as he does not mow the lawn and do things other husbands do. No one says anything of my housekeeping ways for that is inside. But we don’t get visitors.

I suppose from the point of view of weeks (actually it might be a few months) of unacknowledged punishment of her I understand. I did not have her experience: Jim did not lose a job he needed, we are not forced to move (we have not been stupid about buying a house in an world which forces this on you if you can in order to have minimum security — because in most places there is no rent control at all); he has not had horrible experiences in hospitals at all. He has been treated on that edge or cusp of decency. He is know to be an ex-Chief Engineer at DARPA, not a file clerk. That he had the operation first is a key here; we had much much better insurance; he has made much much more money; we have much more in the bank. I am not personally giving up any job myself.

(We are somewhat dreading the coming chemo and radiation.)

Yes the system is responsible for her having nowhere to turn. It has put her in this position. It has given her no help. It has made things worse. It has made her believe that Harvey is also individually misbehaving – by staying in his room and refusing to come downstairs. We could say she doesn’t see it. She has not realized she is taking out her pain on the system’s victim. I have seen the admiral partly ironically as the doctor’s victim — he and I joke about this; it’s the sort of truth we get out through jokes. The admiral said as he was going through the pre-op that it bothered him how every one said what a “perfect candidate” he was for this. A kind of guinea pig. No one remarked he did not have to pay huge sums, but they were glad of the chance to do their stuff and that somehow or other he was in a position to allow them to do it.

We can’t see this indirect connection and that’s how the people profiting (making enormous sums of money) or living middle class lives and afraid to rock the boat (the people with middle salaries) pull it off. The guy trying to cheat them as a handyman is trying to screw what he can out of the rotten system from another angle.

The admiral and I have refused to be co-opted, but we have also been lucky a couple of times and we have bucked the social life and taken the costs there too — our children have paid a certain price growing up this way too.

“She’s not raping and murdering him. She did hit him” – Ellen, clearly you have not looked directly at these images in awhile. That’s not what they show. Look again. The panel shows her hitting him THREE TIMES, the last a PUNCH with closed fist! A helpless dying man! It’s an almost inconceivably horrible act of violence, not anything that’s remotely OK because she had bad insurance and he acted stupidly. Perhaps the problem is that I am seeing this out of context, and you are seeing it within context, so you can excuse the woman because you sympathize with her whole story. You may also be doing some transference, identifying, which is understandable under the circumstances. I only know what I saw, yes out of context, but I ask you to look at this again, not confuse and complicate it with your own experiences and say it’s justifiable because she had a harder time, less money than you did. Just look again, will you? It’s a BEATING! of a dying man!

Yes she’s punching him — and three times. I agree not just hitting. Diana the picture here is shocking and horrifying. I admit I blenched when I chose this picture. I have not seen anyone who discussed this novel who chose some of its tough pictures. The pictures chosen are the ones against the neighbors or someone walking down the street. I have been daring and unusual in printing this set of cartoon frames.

The drawing makes it transcendantly awful. It is an instance of where we see how central to the experience of a graphic novel is the art. Had I not put the picture on my blog it would not have had the visceral response in you it has. We see a huge woman’s figure writhing over her husband. It’s far larger than the real Joyce (who in her photo looks thin). I picked another which does the same kind of thing: the one of Harvey in the shower, an intimate moment where he is thinking of what is happening to himself.

You allow me to point out something else in the art of this novel — it’s a novel. I can’t quite be sure that Joyce acted that way — this is part of the problems of reading a graphic novel memoir.

I also tried for two juxtaposed that suggested the ambiguity of irony: when this woman goes to Israel and Palestine in one set of pictures and the next we see him all alone. I said that there it’s possible irony against her was meant but I didn’t think so because of the larger context of words and pictures.

It’s not justifiable but it’s understandable. Had she had help — someone helping her — she would not have been driven this way. I can’t be sentimental and would say also had she had someone in the house with her that would have mediated her relationship with Harvey and also controlled her behavior.

The book has been the subject of many internet discussions. I found sites of these which I didn’t link in. The discussions have been sore as others suffered what she and I have suffered.

I did say I was put off and appalled by Joyce overall. I really hated the nurse in the chemotherapy room too. Joyce did not protect Harvey there. I would have. She identifies with the system and upholds it. I do not. Nor do I take out what I feel on its victim. I see Harvey as the ultimate victim here.

Many years later he killed himself when he discovered he had cancer for a third time. I understand that. I wish the Internet site had not been coy but told the truth and again hit at the system when it does not.

Thanks for the explanation, and I shall hope it’s fiction!

But I think I’d really rather read something else. ;-( Just saying! I definitely need something softer tonight. Waiting to hear about a friend’s cancer test. And so it goes…

It’s not a comforting book. If Joyce is like how she is portrayed, I doubt she and I could be bosom friends.

I could have gone on about the wholly inadequate grounding of her leftist politics.

I also don’t say that in other societies it’s done much better. Maybe some do help the people involved at least and don’t destroy them monetarily (as ours can).

I doubt one can write a book about the experience of cancer that is honest and comforting – at least as presently experienced in our society.

I imagine it’s possible to write a book about the cancer experience that is honest; sure. But comforting? Probably not. There’s no comfort. Glad you don’t think you could be bosom friends with Joyce; hard to see how.

And I’m glad we have not quarrelled. Are we not like Mrs Gardener and Elizabeth: an example of people discussing a hard topic and remaining together and sympathetic too.

Yup! That’s us. 🙂

Again a good comment about Joyce’s horrible beating up of her husband:

From a friend: I found your blog on the Cancer Year so interesting. Like Diana, I was shocked by the hitting, which, even if it was the acting out of fantasy, was barbaric — and made me realize how at the mercy of an untrained caregiver a sick person is in this culture. People are such bullies — how can a sick person fight back against the one they are so dependent on?-and yes, the writers blame the victim and not the system. People are going to look back at how we ran health care and wonder how it could be this way. I keep thinking, perhaps obsessively, of how even in Nazi Germany, assuming you were a normally healthy Aryan (naturally you’d want to avoid the health care system at all costs if you were Jewish or mentally handicapped or Roma or gay or whatever) but assuming you considered “volk” you were taken care of, allowed to convalesce, treated humanely, because the Nazis largely left the hospital system that preceded them stay in place. But to think you were allowed to convalesce (if you were the right kind of person) in Nazi Germany but not here!

I agree the hitting was horrible. I was appalled. I spoke to Diana the way I did for she wrote about the incident in such as way as to put all responsibility on the individual for what she did. So I said I did understand how one could be driven wild. And for example, I just found out we are paying $245 a week from Equinox no matter what for the pump, pole, bags, isosource and syringes. I needed 5 more bags and got a roundaround all day; was on the phone twice, and if I had not called a third time would have been made to believe it was impossible for me to get just 5 more bags. the people on the phone had insisted the company does not “sell” the bags unless one buys an equivalent amount of isosource. We don’t need any more formula; they sent too much in fact. Well this morning 35 of the bags arrived, a box stuffed with them. From the supplier to Equinox. The $245 a week will stop when we return the pump and pole. So either the people on the phone at first did not understand this arrangement (we are paying as if we were Kaiser so we are to get what we want and need) or they thought they could fleece me for yet more: the demand was I buy more isosource or they were “not permitted” to sell more bags. That’s a system. I am not working, I can afford the sums, I had the time to be on the phone. This was not Joyce Brabner’s case.

But I agree that even in such a horrible system, there was on a deeper level of humanity and truth not only no excuse for her behavior (that’s what I wouldn’t concede to Diana) except maybe her own stupidity which made her buy into this system. Her leftist politics are a laugh to me. She was preying on the system’s victim. And she did it because he was available to her the way people in marriages prey on one another as the closest person. The patient is the system’s central potential victim. And you’re right the lesson one can take away from this is how vulnerable the person is to the caregiver. This has been the occasion of supposed funny French films. In one an upper class rich art critic (man) paralyzed from the neck down is taken care of by a working class colonial black man whose resentment the man arouses, and there are painful scenes (not funny to me) of the black man withholding this or that from him.

Yes I said on one of my Sylvia blogs imagine 200 years from now perhaps people will be horrified to see how we behaved. It would change a lot if there was some cure for cancer or some treatments less harsh. The blog saying this as a whole appalled some of the readers of the Sylvia blog, shocked them … especially one woman whose husband died of cancer. Perhaps she has invested into the idea he had the best care possible; she really believed in these “support groups” for individuals. They are capitalism’s way of disguising the fundamental situation.

An acquaintance who has had 3 recurrences of cancer and some dire treatments wrote me to say she read the blog with interest (a 5 year [!] roller coaster, she called it); thanked me for sharing; and said she understood the need to write (she kept a diary on radiotherapy treatment). Also how she had to drop one of her positions.

I replied as follows:

Dealing with cancer is time-consuming 🙂 I’ve had to drop a couple of projects (planned papers) and my work goes slower. I wanted to reach people too, specifically friends (which for me includes cyberspace friends) and write in the way of Burney: to the moment, partly in order not to forget.

Dire treatment: cancer is such a harsh disease if not treated, people are willing to undergo, and doctors certainly to try dire treatments. The effects on people should be better known and made public — the way disability effects need to be talked about. It might have the very gradual effect from the medical establishment of improving their behavior to patients in the sense of acknowledging what they are doing to the patient and genuinely helping patients and caregivers to cope. Right now from the medical establishment there’s zilch accommodation. Maybe it’s better in Britain but I lived there for over 2 years and found outside of the important area of payment (which does affect lots of things) attitudes towards patients were analogous to those in the US.

Have you ever seen the movie, Wit — Mike Nichols and Emma Thompson. I don’t recommend it if you get upset watching movies of people suffering from cancer but it is a useful movie in this way. I showed it to students repeatedly over the years whenever I taught Advanced Comp on the Natural Sciences and Tech.

My husband has had one dire treatment and is now dealing with immediate aftereffects. We don’t like to think he would have to have any more such operations.

Ellen

I tried to watch American Splendor last night and found I disliked it. What is acceptable in a graphic novel is not necessarily acceptable in a movie. I know Posy Simmons’s Tamara Drew was changed a lot when it was turned into a movie; there was a reaching back to Hardy and use of costume drama techniques. Not here. AS was to me irritating; the central focus on the protagonist so self-involved in these graphic novels became sheer egoism. This time Harvey does dominate but he comes across as (to me) grating as Joyce: yes they defy US taboos. He wants a job as a file clerk and nothing more. He wants free time; he wants to work on his writing and doesn’t care if it does not make a lot of money — supposedly. But if you watch, you see how he buys into the values that undergird this chase for materialism, prestige, money; he just makes less. This is the world of the lower middle class in NYC (Kew Gardens) as I remember it.

I was going to say I’m going to be frank. But when am I not? (Actually I’m no where as frank as I make out). I detest Joyce in the book, I was continually grated upon by her. I didn’t want to say so because I suspect what I’m disliking is also a memory and response to Jewish culture as I knew it growing up in NYC and I disliked it intensely — especially as embodied in my mother and her ways and comments. I disliked how she got all upset about Harvey losing his hair. Who the hell is she? it’s not her hair.

It may be the only way they could present the awful humiliation of losing your body hair is through the other person; the cancer person cannot communicate what he’s feeling inside; it seems too egoistic. But he does that in the movie. In the comic book they kept him seconary.

I don’t know that there is a study of the genre of graphic novels but when I saw the movie, I began to like them less.

Ellen