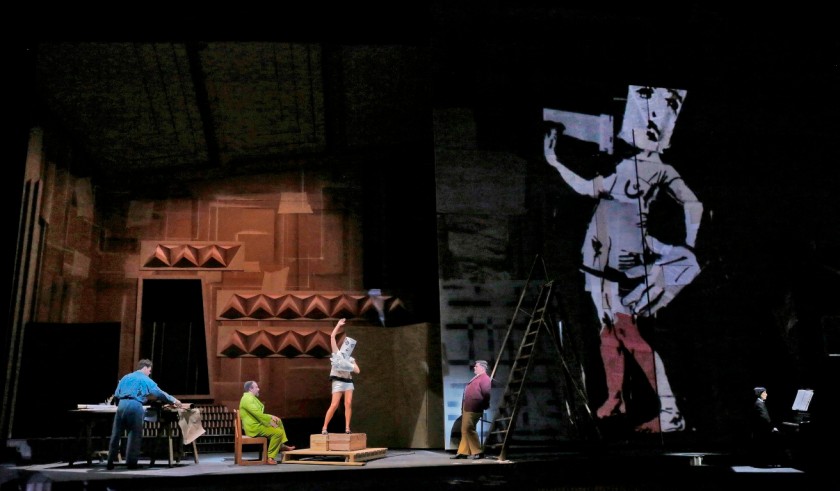

Opening scenario to Berg’s Lulu (designed by William Kendrick, directors Luc De Wit & Matthew Diamond

Dear friends and readers,

I’ve put off writing about this opera for a few days in order to hear what others who saw or heard it might say, to read reviews and find out about its sources because I had such a mixed reaction to it. First the story, which should be told (because it’s meant to be) crude/ly:

Lulu is a highly paid prostitute, actress, dancer, model kept by Dr Schon a physician who also supports a painter painting her continually. In comes Schigolch, her once abusive beggar father and she gives him money. She is aggressively “in love” with Dr Schon who says he wants to marry a rich socialite.

Lulu (Marlis Petersen) and Dr Schon (Johan Reuter who also plays Jack the Ripper)

Alwa, the physician’s son enters, enthralled by Lulu, who in the next scene has married the painter who kills himself when told of her past.

Lulu and painter (Paul Groves)

In the next act, in a ballet Lulu has danced in off-stage, she has exposed her relationship to Dr Schon to his fiancée; and faute de mieux he marries her. A boy scout or schoolboy (who I feared for) comes in admiring them all. An older countess-patroness Geschwitz, a lesbian, also loves Lulu who exploits her. Quarrels ensue, Dr Schon wants Lulu to kill herself so he will be rid of her, and in a fight, she shoots him several times. Son, countess, beggar father, boy scout try to cover up, but she goes to prison. She emerges shattered, thin, in a catatonic state. Son loses all his money in a scene with a crooked banker and investors. She ends up a ragged street prostitute in her efforts to support them all:

Again, Lulu and Alwa (Daniel Brenna)

She brings men in and out, haggling with them for money; one attacks and kills the son, Alwa, but another turns out to be Jack the Ripper who (after she argues with him for more money) offstage murders her. Ripper returns to knife to death the despairing countess who cries out for Lulu.

The countess Gerschwitz near the end (Susan Graham)

****************************

As it began, I disliked it because of the grotesqueries, and repellent imagery of a woman’s private parts garishly drawn on allegorical costumes and in flashing shows of light across the stage:

Lulu as we first see her costumed

But as the whole experience sunk in, or by the third act, while I continued to be distressed by the images of women’s private parts and breasts, I was shaken by the what was happening to the characters especially after the murder of the doctor as a farcical tragedy about the restless misery of personality-less individuals caught up in some maddened nightmare. I could find little to like in the music, hardly any melody, continual noise like hip-hop spoken rock, only the voices were singing and deeply resonant, plangent.

In this desperate crass bleak environment now and again a few yearn for happiness, peace, seem even to have an inkling of what this is: the painter who kills himself; Schigolch, the beggar dependent on Lulu for money sung here by Franz Grundheber; Alwa, Schon’s son; a naive schoolboy; the lesbian Countess. Most spend their hours vaunting themselves, behaving arrogantly or guardedly, coolly, seeking to marry or have sex with the richest most powerful person in the room, mocking other people, lying, cheating: Lulu; Dr Schon also tellingly the serial killer, Jack the Ripper; also an Animal Tamer, an Acrobat, an African Prince, a crooked banker, nameless investors and party-goers, not to omit two allegorical characters, a creepy man and sullen woman dressed in elegant evening clothes:

By the world’s chances (the play was begun just before and during the early Nazi period when the mark had lost most of its value) and their own venal stupidity in following a Banker who is a stock market crook, they become destitute, whereupon they grimly hang on to anyone who will prostitute herself, in this case, Lulu. The norm throughout is sadomasochistic sex.

Lulu with a male who is after her — the norm is sadomasochistic sex

Sometimes one person was the bully and the other abject, and then they’d change places. No one ever looked content; cheerfulness is out of the question: dark, intent, intense.

It may be the designers did not have the courage to flash up male private parts (as more shocking and less acceptable than female?), but if this omission was cowardice, the effect was sexist and eerily women-body-hating. But by the time the opera was over I was persuaded the wild use of lights, computer pictures in black and white of anguished, naked, violent, raging figures, sexism, and screens all over the stage, over-the-top theatrical imagery was justified effective expressionist projection of passions kept hidden, coming out only subtly but what drive the world’s overriding social structures.

*************************

The stage

My friend, Fran, supplies the sources, background, artistic milieu: “It is based on, Frank Wedekind’s Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box. Wedekind later conflated both works to the five act tragedy Lulu, which I have seen performed and which once seen is not easily forgotten. Apparently it was his original intention to write a single play all along, but his publisher initially got cold feet.

Wedekind was a German who grew up in what was the equivalent of Victorian England, and he would satirize and attack bourgeois capitalism, pseudo-morality, artistic philistinism, prudery and double standards etc. Stylistically he was influenced by Georg Büchner and was, like him, very much ahead of his time, being a precursor of the Expressionism you mention, but also the Theatre of the Absurd and Brecht’s epic theatre, for example. The latter cited both Büchner and Wedekind as direct inspirations and wrote the latter a laudatory obituary when he died in 1918. (Berg’s other famous opera happens to be Wozzeck, originally a Büchner play itself.)

Berg himself first became acquainted with Wedekind’s Pandora’s Box when he saw a private performance of it in Vienna in 1905. Wedekind himself played Jack the Ripper and his later wife Tilly Newes was Lulu. Only closed, private performances were allowed by the censors Wedekind’s work was always falling foul of. There is an available picture of Wedekind playing Dr Schön to Tilly’s Lulu in performances of the Earth Spirit. Berg has a singer doubling the roles in his opera, too.

Berg started writing his own piece in 1927. It was originally to have been performed under Erich Kleiber at the Berlin opera, but shortly after an orchestral piece culled from the existing parts of the opera had been performed there in 1934, the Nazis forced Kleiber to resign and Berg postponed finishing the opera in favour of a violin concerto. His death in 1935 meant the opera remained unfinished until Berg’s music publisher commissioned the Austrian composer, Friedrich Cerha to use Berg’s surviving notes to complete the third act in the 1960s. This version wasn’t presented to the public until 1977 and thus 2 yearsafter Berg’s widow’s death, since she had always opposed the procedure. This three act version had its premiere at the Paris Opera in 1979, directed by Patrice Chéreau and conducted by Pierre Boulez.”

Izzy, my daughter who came with me, said there are few atonal operas; atonal music was written in the middle 20th century, admired by academics, but never gained a wide audience.

**************************

Lulu with her beggar father, Schigolch (Franz Grundheber)

Fran sent along URLs to two excellent essays: “danger and desire” in the Huffington Post; “modernism in Lulu” from Yale.

I found a couple of favorable and sympathetic reviews of this production: “desperadoes” in the New Yorker; and “the question that stops the opera” in the New York Times.

The talk in the intermissions was not as stupid or hyped as usual which was interesting in itself; Grundheber was intelligent about the opera; others spoke of the difficulty singing it; others were uncomfortable about their characters (Susan Graham). But the question Deborah Voigt (following a script) posed and the New York Times repeats was misleading though it’s what the audience is thought to be left asking: is Lulu victim or victimized? Suggesting some of the actor-singers did not see any larger picture, but instinctively wanted to defend themselves against the idea the opera is unfair to women: Reuter (Dr Schon and then Jack the Ripper) pointed out in reply how Dr Schon was a bad man, guilty and was punished (!).

This makes us look at the female to find punishment or rewards, so erases one of the opera’s strengths: here is no Traviata, no Wagnerian self-sacrificing utterly devoted woman who dies for her men, or seethingly evil femme fatale or witch. Our heroine who began as mechanically aggressive and cold becomes mechanically withdrawn.

Rather all the characters are remnants of a terrible world outside the claustrophobic spaces we see them in, thrown out of some whirlpool of imbecility just outside the door. They come in staggering. Were it not for the screens, the acted areas would be small dark bare places. The one scene where we see the crowd, at the close of Act 2 in this production, is when the investors follow the banker about; just like the investors of Trollope’s The Way We Live Now, they are greedy, indifferent to what their money was put in, ignorant of the workings of money and deluded. The opera is important: produced on such a scale for prestigious place says something: the content that is here pointed to is the extraordinary frankness with which sexuality is dramatized, how this prefigures other relationships. If you have not had anything like these experiences as a viewer you might be put off. What was implied about sex was the most troubling aspect of this production.

Finally, it’s remarkable to realize how modern we think this opera is and yet it’s 80 years old. That suggests modernity hasn’t penetrated the mainstream arts very much. Among the women in the class at American University I teach, two women said they had gone to the opera: one (like Izzy) left after the first act, and (like Izzy) thought the production misogynistic: the woman pointed out that we saw Lulu jump on the doctor, Lulu wrap herself around him, Lulu as animal and not the doctor. The second woman in my class left after the second act, and complained (like me) of the drawings of woman’s private parts thrown up on the screens as “repellent,” and said she did ask herself, why there were no men’s private parts? When Izzy left, I got up to sit elsewhere as a couple behind me had been quarreling with someone else over their seats. Three women behind me asked if I was leaving like my daughter. I said no, just moving away from the quarreling people. They looked relieved and asked me what I thought of it. I said, well I want to stay to the end to see how Lulu is treated when a prostitute. One of these women then said she found it compelling; the second said it was relief not to have these self-sacrificing virtuous heroine; another (echoing my silent thought) that she was tired of Traviatas. On face-book when I briefly described the opera, one woman said it “sounds pretty dreadful.” Another that she was glad she would have no chance whatsoever to see it.

The one male I did talk to about it commented: “A shame nobody does Jeffers’ version of Medea anymore. He turns Medea into a hero.” He was referring to the great American poet, Robinson Jeffers. A woman poet friend just said she liked the opera.

So, did I enjoy it? no. Would I go again? no. But I’ll remember it. When I’ve read Euripides’ Medea, I’m with her until she insanely kills her children.

Ellen

Kenneth Graham:

“Dear Ellen,

I’m one of your many silent readers on the opera. I saw my second Lulu last Saturday and enjoyed your comments, both your own impressions and the account of the opera’s history.

I seem to have missed all the genitalia but the opera left me depressed for the rest of the evening.

The Met, as usual, were thorough and perceptive, but I’m glad it’s not performed often.”

Dear Kenneth,

I’m especially honored since I’m a reader of your collection of essays on the gothic..

I felt a certain trepidation with this one: I don’t know enough about German literature and am no expert in atonal music. So that’s why I waited until I could gather decent information, and good essays to point people to. It’s a significant work and I commend Gelb for doing it. He so often opts for the safe in the HD series so when he stretched his neck out with Klinghofer and now this I wanted to call attention to the work.

The opera did leave me shaken. My absolutely anecdotal evidence is women were far more aware of the genital imagery and distressed or upset or grated upon (one women left of my tiny group who said that, I expect my daughter also didn’t like it) than men.

Yours and a couple of comments off-blog made me think about this. Maybe the opera is 1930s. Nowadays we would be aware that this is a narrow population Berg is sending up: yes expose the bourgeois untruths and hypocrisies but we wouldn’t get so angry because we’d be more pluralistic, more post-colonial, not so upset by how the mainstream media ignores porn.

I love Haydn, Handel, Mozart, Beethoven so also missed music that “glides into the soul” (Johnson quote).

Hi, Ellen, I think Lulu is a masterpiece and Kentridge’s production is brilliant. Having only seen it in HD I regret missing what must have been the impact of the projections in the house. I would see it again in a minute. I am surprised that you didn’t comment on the singing and acting, which were astounding; Marlis Peterson gave one of the most remarkable performances I have been privileged to hear and see. The orchestra was great, too.

As Dr Schoen states explicitly, Lulu has been groomed from the age of 12 to be an object of desire. The opera is about the commodification of women and the degradation of sex. Yes, there were depictions of breasts and female genitalia, but as I understood it, they are the (perverse) blazon of Lulu, in the old sense of an enumeration of beauties; the canvas of the projections and even the other characters in Act 3, when they are dressed as versions of Lulu, are a visual catalog of her physical attributes. Kentridge fragmented the iconic portrait of Lulu that is described in the original to echo her dismemberment by her culture, by her lovers, and ultimately, literally, by Jack the Ripper. (Normally the portrait is a large conventional portrait, e.g., of Lulu as Pierrot.)

To show naked male bodies would, I think, have palliated the harshness of the critique of the objectification of women. The mechanization of the imagery (including the mimes) helped to insure that one was always aware of the corruption of those images and the way Lulu was being used (and, self-destructively, using).

I wish the HD telecast had spent more time exploring the technology and artistic component of the projections. I can skip the interviews with the singers.

Lisa Berglund

A photo someone much closer to the stage or at the Met itself managed to get of the principals — they look much more human here — all mine are stills from an HD-screening

Dear Lisa,

Thank you for your reply. Though my readership is comically small in comparison to commercial individual and of course institutional sites, still I get something like 500+ a day on average so others will read your remarks.

I didn’t go into the individual acting. I felt the costumes, paper hands, masks, meant me to see the people on stage as types, and the screens had the effect of distancing the viewer from the performers. Realism or naturalism was not wanted. I thought Petersen remarkable: I did comment on how she conveyed mechanical gestures; she was deliberately over-the-top in her misery and jarring moods. Reuter seemed to me embarrassed. Graham was the most naturalistic. I agree the interviews are often a total waste, but in the movie-house I watch them and they can be revealing. Reuter didn’t understand the opera; and Grundheber did.

We’ve talked at conferences, and I’ve listened to you and others talking on modern operas (once with Douglas Murray) . I’ve not seen any where near as many as you; Jim and I didn’t travel to these. He would have appreciated the music, at least understood it. I was similarly honest about my response to the imagery. I probably would have done better with the plays — so included the information about these; and also to elucidate the opera.

I understood it was an expose of the way women are treated today, but felt why not expose men too, and anyway it distressed me. Why not expose men’s private parts? I feel it’s that these people think of women’s bodies as what is to be exposed, not men’s, like a reverse of the burka almost. I hear you that this is critical display, but I wonder how it’s taken and if it was critical truly. It was quite a walk home for my daughter and she left — she majored in music at Sweet Briar and it was she who had wanted to come to this one. I thought the woman who suggested the direction made Lulu into an animal and not Schon was accurate.

Ellen

Clare; “I heard a passage at my music conference this weekend. Funnily enough the speaker I had to introduce and thank this afternoon at a lecture also played a passage from the Mercury recording of Lulu, where the lesbian bemoans the death of Lulu. It’s powerful stuff. The story is strong meat too, not to everyone’s taste, but I love it. It was an astounding sound world, and I really want to investigate more.”